A collector’s guide: Early Daniel Roth

The curiously shaped watches of Daniel Roth would certainly catch your attention if you spotted one on a wrist. In fact, they would probably make you move closer still.

For a few years, the watchmaker produced pieces that offered a creative and playful take on the work of Abraham-Louis Breguet, combining double-ellipse cases, hand-finished details and an inventive approach to classic complications.

During the late 20th century, a range of independent watchmakers decided to start producing watches under their own name, usually following a period spent developing calibres for other brands, or restoring vintage pieces. Names such as Roger Dubuis, Franck Muller and Vianney Halter frequently come up when this new dawn of contemporary independents is discussed. Indeed, Daniel Roth was amongst the first to venture out on his own, establishing his eponymous brand in 1988, more than ten years before François-Paul Journe would do the same.

On the agenda

The path to watchmaking | Under his own name | The core principles | The core collection - The tourbillon C187 - The chronograph C147 | The rest of the collection - Back to simplicity with time only models - Developing the perpetual calendar with Philippe Dufour - The final models | Daniel Roth today

One of the very first watches Roth produced, a tourbillon numbered 00, courtesy of Christie’s.

He released a range of noteworthy pieces, from the classic tourbillon, to a perpetual calendar developed in collaboration with Philippe Dufour, before he gradually became less and less involved with his brand. His ownership was diluted over time, culminating in the sale of the company to Bulgari in 2000. Today, Roth produces one-off creations under the Jean Daniel Nicolas name, working closely with his wife and son, completing around three pieces a year.

As one of the first independents, we thought we’d look back on the early days of his work, from his training at Audemars Piguet, to the resuscitation of the Breguet brand, all of which culminated in him setting-out on his own. During the process of putting this article together, we’ve been lucky enough to draw on the knowledge and insight of several individuals who have followed the watchmaker’s work closely, including a second-generation Roth collector and someone close to the man himself. Let’s have a look at where it all began.

The Path to Watchmaking

Daniel Roth was born into a watchmaking family in Nice, France. His grandfather and great-grandfather were both watchmakers in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Before he was born, the family moved to the south of France, opening up a small repair shop where he would spend much of his early childhood. Considering he was surrounded by watchmaking paraphernalia whilst growing up, it made perfect sense that Roth should eventually attend a three-year watchmaking course in Nice.

A younger Daniel Roth before he established in eponymous brand.

Upon completion, he traded-in the sandy shores of the French Riviera, for the snowy slopes of La Valleé de Joux, where he would take up work at a range of different manufactures, including Jaeger-LeCoultre. However, it was at Audemars Piguet that Roth would develop his skills, spending the next seven years working in Le Brassus. According to Roth, he was the only watchmaker working there who didn’t come from the brand’s historic home, and so they kept a particularly close eye on him.

It was after he began to blossom at Audemars Piguet that another opportunity arose for the young watchmaker. Jacques and Pierre Chaumet, the owners of the eponymous jewellery brand, had recently acquired Breguet. In the midst of the Quartz Crisis, they wanted to restore the brand to its former glory and were looking for a Master Watchmaker who could help. When applying for the role, Roth made a rather unusual choice – he sent a two-page CV, one page detailing everything he knew and another detailing all the things he had yet to learn. This brazen honesty clearly impressed the Chaumet brothers and François Bodet, the Director of Breguet at the time, as they decided to hire him.

The pocket watch Roth produced when he went back to school before starting at Breguet, from Daniel Roth via Quill & Pad.

Evidently dedicated to his craft, Roth decided to go back to school to further study Breguet’s archives and techniques, a decision he made entirely by himself, rather than it being a requirement imposed by his new employer. During his year of further education, he learnt everything he could about Abraham-Louis Breguet, a watchmaker who had pioneered significant technical and aesthetic innovations throughout his career. Breguet spearheaded a number of inventions, including the overcoil hairspring and the tourbillon, which he first invented in 1795 and patented in 1801. At the end of his year of study, Roth produced a perpetual calendar pocket watch, which was then sold to help offset the cost of his studies in Le Sentier. Finally, in 1973, he was ready to take-on the task of reviving one of the most storied names in horology. No small task.

At this time, Breguet was still very much a French brand. Their production took place in France and their only store could be found, as expected, in Paris. Unfortunately, the centre of watchmaking had moved away from the French capital, and now firmly resided within Switzerland, where the finest watchmakers and suppliers were based. Roth knew that if he was going to bring the Breguet name back, he would have to move their watchmaking operations to the Valleé de Joux. As such, he helped the brand establish a workshop in Le Brassus in 1976.

The Lemania factory that would eventually become part of the Breguet manufacture, courtesy of Monochrome Watches.

During his fourteen years at Breguet, Daniel Roth and François Bodet worked together to define the Breguet aesthetic in wristwatch form, as well as introduce a range of new models and complications to their collection. The engine-turned dials, coin case and distinctive Breguet hands became signature features of these pieces. From perpetual calendars to tourbillons, they embraced the high-end complicated watchmaking first personified by Abraham-Louis Breguet.

Highlighting some of the key design elements the Roth brought back to Breguet, courtesy of Baruch Coutts.

To power their watches, Breguet would make the most of Lemania and Frederic Piguet base movements. A prime example of this is the perpetual calendar reference 3130, a long-lasting model which was first designed by Roth and Bodet, having been directly influenced by the No. 5 pocket watch that Abraham-Louis sold in 1794. This modern reference was introduced in 1983, using a movement based on the Frederic Piguet 71. Roth also chose to emphasise the hand-finished craft which had been so important to Breguet back in the day, with the Clous de Paris pattern on the dial, applied by hand. The automatic perpetual calendar was released in 1976, almost a decade before Patek Philippe would begin producing an automatic perpetual calendar in series.

A selection of models that Roth and Bodet introduced during their tenure.

In his fourteen years there, Roth helped to restore the Breguet name. However, his time at the company came to a dramatic end following the downfall of the Chaumet brothers, who were the ninth generation of their family to run the maison. After seeing a spike in the price of diamonds, Jacques and Pierre began to offer individuals and banks the opportunity to buy diamonds, with the promise of a significant return on their investment.

A report on the Chaumet brother’s downfall in the New York Times.

Unfortunately, they didn’t predict the quick drop in diamond prices which took place in the early 1980s. Instead of cutting their losses, they doubled-down and allegedly defrauded the clients who’d invested with them. This eventually came out when a few of the banks involved complained about not seeing any returns. The French government forced the brothers to declare bankruptcy after Chaumet had amassed around $120 million in debt to 12 different banks. As part of the bankruptcy declaration, the Groupe Horloger Breguet was sold to Investcorp in 1987. A year later, both Roth and Bodet, the two most responsible for the Breguet’s comeback, left.

Under His Own Name

The year is 1988 and Roth is ready to launch his own brand. At the time, the idea of independence was quite far fetched, with no one for Roth to look up to for guidance. Despite this, he had a clear vision for the kinds of watches he wanted to make, as well as how he wanted to go about producing them. His time at both Audemars Piguet and Breguet had been transformative. He had seen how larger brands were able to produce different models in series, whilst keeping their relatively high standards. Roth would set-up shop in the town of Le Sentier, at 37 Rue de L’Arcadie.

A Daniel Roth advert from his 1995-96 campaign, courtesy of @ciaca70.

Working on his own at first, Roth sought to introduce a coherent collection in his first few years, including several complicated and time-only models. The watchmaker was able to establish the brand in a few key markets, notably Italy and Asia, where he would find relative success. It speaks to the geographic reach of Roth’s work that an early manual we came across, features instructions written in English, German, Italian and Japanese. By 1992, just four years after getting started, Roth already employed twelve watchmakers. During this early period, production numbers were relatively limited, driven by the brand’s commitment to traditional production methods, like hand-finishing dials and painstakingly decorating movements.

Two of the more recognisable model that Roth would go in to produce.

Struggling to drive the brand forwards on his own, Roth decided to take on external investment. In 1994, he sold his managing stake to a new investor, looking to take things in a new direction. This involved an increase in production numbers, with the manufacture employing thirty watchmakers by 1995. The design of the pieces also began to shift towards a more contemporary and sporty aesthetic. Overall, under this new stewardship, things seemed to gradually move away from the watchmaker’s earlier vision. Despite not being a majority shareholder anymore, Roth himself remained involved in some capacity. In 2000, the company was eventually sold outright to Bulgari, with Daniel Roth leaving one year later.

An early Roth tourbillon with one of his more contemporary pieces made under the Jean Daniel Nicolas name.

The Core Principles

Across all of Roth’s early work as an independent watchmaker, there are a few core principles that stand out. These speak to his vision and what he was hoping to achieve with his young eponymous brand. Before looking at the individual models he produced more closely, we thought it was worth surveying the key characteristics that tie all these early pieces together.

The fourteen years Roth spent at Breguet, and the preceding year he spent studying Abraham-Louis’ work at school, clearly had an impact on him. In many ways, his work offers a creative take on traditional, Breguet-inspired design. With hand guilloché dials, blued steel hands and carefully crafted precious metal cases, the lineage with the master watchmaker’s work during the 18th century is obvious. It’s interesting to think that Roth was responsible for translating the Breguet aesthetic into wristwatch form when he was involved with the brand, and then adapted it, once again, when he started designing pieces under his own name.

A clear continuation of design language from Roth’s work at Breguet with this 3237 to his own brand.

Beyond the obvious stylistic cues, the continuity with Breguet is also apparent in more subtle ways. Roth proudly numbered many of his early pieces on the dial, something which Breguet often did with his own pocket watches. A rather unusual design choice for a modern wristwatch, one can imagine that this was meant to proudly highlight just how limited the independent watchmaker’s production was. Of course, Roth didn’t only carry-over design choices, but also techniques. A high level of hand-finishing can be found across his early work, from the dials to the movements themselves. He often chose to highlight this by creating open-work and hand-engraved versions of his models.

Displaying the numbers on the dial is a rare sight in modern watchmaking.

However, Roth’s work wasn’t just about imitating what had been done in the past. There was clearly an evolution and innovation in design, which moved beyond Breguet, into a more contemporary direction. Firstly, Roth introduced a completely different case shape, which has become one of his signature elements. His double-ellipse case was neither round nor rectangular. Rather, it balanced the two different shapes, complemented by a stepped bezel and sharp, straight lugs. If you compare it with his work at Breguet, you can see that some of his design choices were transferred, such as the straight lugs, sloped bezel and polished finish throughout. Overall though, this was a decidedly bolder direction.

The distinctive shape of Roth’s case was a new concept for the watch industry, courtesy of Keystone.

Furthermore, Roth also made a range of more subtle design choices throughout his early work that speak to his more unusual, distinctive vision. For example, his tourbillon integrates a triple-armed seconds hand, where three blued steel hands of varying length, glide over three different seconds registers. Despite being powered by the same Lemania ébauche found in the pieces he created whilst at Breguet, his own tourbillon is decidedly more adventurous. The layout of his perpetual calendars is also anything but traditional, with a novel distribution of the different indications. What about case materials and dial colours? Plenty of variety here too. Roth used yellow, rose and white gold, as well as platinum, and occasionally steel. He also produced a small number of two-tone pieces along the way. As for the dial variations, these are too numerous to number, though he did integrate colours from salmon to electric blue, with various different combinations found throughout his body of work.

A final element that he brought from his years at Breguet was the reliance on high quality ébauches, mainly from Lemania. Indeed, his chronograph, tourbillon, perpetual calendar, minute repeater, as well as a range of his time-only models, were all built on reworked Lemania movements. Though brands these days have focused on bringing movement production in-house, this reliance on external movements actually speaks to Roth’s commitment to quality. For an extensive period of time, manufacturers from Patek Philippe to Rolex, relied on high-quality movement ébauches created by external suppliers. Many of the other early independents also chose to rely on base calibres produced by Lemania, with Roger Dubuis being a typical example. When he left Breguet, Roth was granted permission by the then owners of Nouvelle Lemania, Investcorp, to use their ébauches.

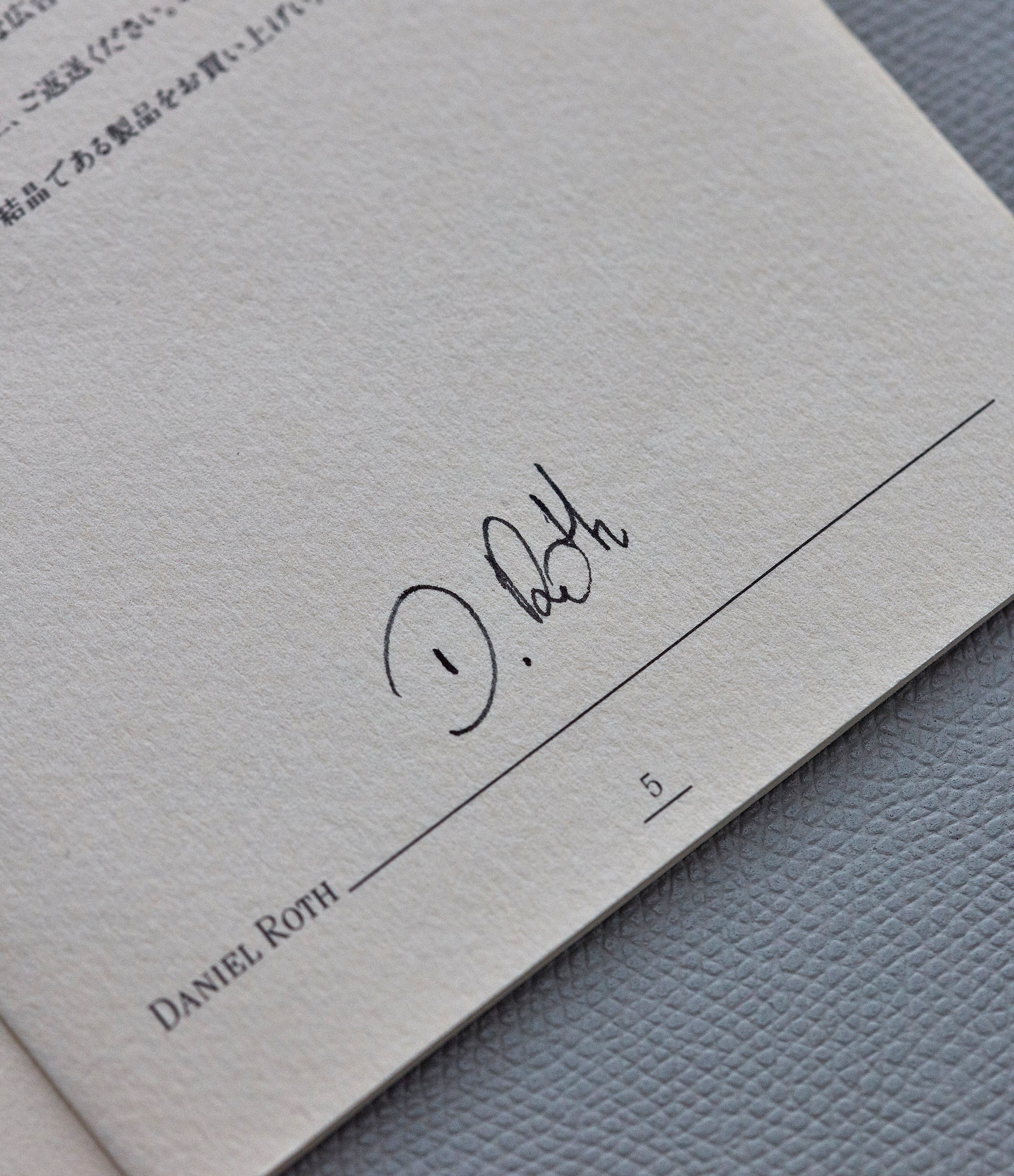

Some of the paperwork that would have come with your early Daniel Roth that included the watchmaker’s signature.

What Roth was trying to achieve with his eponymous brand is relatively obvious. It was a continuation of the work of Abraham-Louis Breguet, which is clear in the styling of his pieces, the classic complications he chose to create and the emphasis on hand-finished details. However, there was also, certainly, a healthy dose of innovation, with Roth cementing an aesthetic that was distinctively his own, much more contemporary than anything Breguet, the man or the brand, had created. As we hopefully now have a sense of the guiding principles of his work, let’s take a closer look at the early models.

The Core Collection

Daniel Roth started his company in 1988, designing and leading the production of many of the early models released under his own name. From around 1995 onwards, the watchmaker became much less involved, as the majority of the brand’s ownership changed hands. From this point, the aesthetic and mechanical focus of the pieces produced under the Daniel Roth name shifts radically, such that collectors of early Daniel Roth tend to pay particular attention to the period between 1988 and 1995.

As such, we’ll focus on the models released during this initial seven-year period, which arguably represents the clearest incarnation of the watchmaker’s vision. First, we’ll spend some time on the tourbillon reference C187 and chronograph reference C147, the first two models he released and arguably the two pillars of his collection. We’ll then look more closely at some of the other pieces which we feel are particularly worth paying attention to, from a perpetual calendar designed in collaboration with Philippe Dufour, to his elusive minute repeaters.

A classic example of one of his early tourbillons.

Between 1988 and 1995, a number of important Roth collectors estimate that the brand made between 2,500 and 3,000 pieces, across all metals and configurations. Considering production only began in any significant way in 1989, this means that Daniel Roth would have produced no more than 500 pieces a year during this early period. As a frame of reference, it’s estimated that F.P. Journe makes around 800 to 900 watches a year today.

The Tourbillon C187

There is something to be said for rites of passage, and in the independent watchmaking world this often appears to be the tourbillon. Tackling the complication has become a way for many young watchmakers to make a name for themselves, with Roth being one of the first to approach it, as part of the wave of independents that took form towards the end of the 20th century. Another notable example is François-Paul Journe, who financed the inception of his brand by creating twenty Souscription Tourbillons, about ten years after Roth. The visual appeal of the complication, its storied past and the skill needed to assemble one according to more traditional methods have all contributed to this.

Roth’s unique triple seconds hand mounted on top of his tourbillon.

For Roth, the significance of the tourbillon was also deeper, considering the complication was first invented by none other than Abraham-Louis Breguet. He designed his double-faced tourbillon, the reference C187 in 1988, and released it in the following year. The foundation for his tourbillon was the Lemania 387 ébauche, which Roth conceived himself earlier on in the decade, when Breguet and Nouvelle Lemania were working closely together. At the time, Nouvelle Lemania supplied Breguet with the majority of their movements, so Roth cooperated with them closely when developing new models and complications. It’s understood that the design for the Lemania 387 caliber came from Roth, with Nouvelle Lemania offering the skills and tools to create a working prototype and then serially produce the movement. Therefore, whilst Roth’s tourbillon was technically based on a Lemania ébauche, it is believed that he was actively involved in its design.

Unlike Journe and Breguet however, Roth didn’t opt for the Souscription model to get his young brand off the ground. Instead, he sought a patron of sorts and found one in William Asprey, the then owner of the eponymous retailer based in London. The Englishman was known as an early adopter of many independents. For example, in 1987, Asprey commissioned three Sympathique clocks from a young Journe, who’d only been running his workshop for two years.

Adding his name to the watches he sold was something William Asprey became known for, and Roth’s pieces were no exception.

In the early 1990s, Asprey placed an order for 24 tourbillon wristwatches with Roth. A testament to the significance of this order, these pieces have the Asprey signature on the dial and the Daniel Roth name on the back. A few of these have appeared publicly, all of them made out of yellow gold and bearing low numbers on the dial, such as “5”, “10” or “18”. It is unclear whether these Asprey pieces were the first tourbillons ever made by Daniel Roth, though they certainly are amongst the earliest. In 1991, he also made a seemingly unique piece for Türler in Zurich, which is skeletonised throughout and features an integrated bracelet, clearly showing he shared close links with some key retailers early on.

All early Daniel Roth tourbillons feature a similar design, with sapphire crystals on the front and back, with the reverse of the watch displaying a date and power reserve. On the front, the C187 features an elongated bridge and an unusual fan-shaped seconds track, with these indicated thanks to three hands of varying length, which are attached to the tourbillon cage.

Just some of the potential configurations that can be found on these early tourbillons.

Whilst the early tourbillons produced for Asprey feature a consistent aesthetic, Roth gradually expanded the designs available. It appears that he offered a range of different dial and case combinations during the early days of the brand, such that a rich array of different configurations exist, many of which have never been shared publicly. Roth used Clous de Paris or a pinstripe texture on his dials, with the former appearing more rarely. It is broadly understood that the Clous de Paris is primarily found on earlier pieces, with the pinstripe used later on. This guilloché is commonly found in an off white, light grey or yellow gold colour, with the last one being the rarest. Openworked and hand-engraved versions were also produced, with the latter foregoing the power reserve and date indicator on the back.

As an example of the more unusual combinations which exist, we’re aware of a tourbillon which was produced with a smooth enamel front and back. On the front, the hour, minute and seconds indicators are displayed in black, whilst the rest of the dial is white, essentially creating a two-tone panda dial. Speaking to the rarity of this model, the only example we’ve been able to find publicly is numbered “01” on the dial. It is believed to have been made for Carlo De Benedetti, a notable Italian industrialist, who supposedly ordered several custom pieces from Roth, including a chronograph and a perpetual calendar with the same design. Roth also produced skeletonised versions of his tourbiilon, introducing the double face version in 1992 and the single face variant in 1995.

Included with your brand new Daniel Roth tourbillon would be these detailed instructions on the unusual timepiece.

As for the case metals, it was principally available in yellow, rose and white gold, with a few platinum pieces having equally emerged. Rather unusually, twenty pieces were also produced in stainless steel. These were made on the request of Roberto Carlotti, the distributor for Daniel Roth in Italy. At the time, Italian collectors had a propensity for steel watches, because of the versatility and wearability of the metal, a taste which was likely born out of their habit for collecting vintage timepieces. The unusual combination of a tourbillon and stainless-steel case, as well as the limited production number, has made these twenty pieces particularly sought-after amongst early Roth collectors.

It’s worth noting that the Daniel Roth tourbillon was the only one produced at the time which was controlled and officially certified by, the Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres, or COSC. This testing institute is responsible for certifying the accuracy and precision of Swiss watches, with the early tourbillons usually being accompanied by a COSC bulletin.

The Chronograph C147

In 1990, a year after Roth started selling his tourbillons through Asprey, he released two subsequent models, which hinted at the first steps of a coherent collection. These were manually-wound chronographs and an automatic time-only models. As with his tourbillon, Roth used a Lemania ébauche for his chronograph, the 2320. This placed it alongside other chronographs from the period which used a similar base calibre, such as the Patek Philippe 3970 and Roger Dubuis's chronographs. Roth had also previously used the ébauche whilst he was at Breguet, integrating it within the reference 3237.

Some clear similarities between the Roth chronographs and those of his design at Breguet.

The two-register, manually-winding chronograph became one of the brand’s most popular models and, as such, was executed in a range of different configurations. Once again, we find Clous de Paris and pinstripe pattern dials, with the former being used on earlier pieces. The most commonly found dial finishing was the pinstripe pattern, which these early Roth pieces have become known for, and the Clous de Paris style guilloché also appears, though much less frequently.

A handful of chronograph variations that Roth produced.

The hand-turned patterns were executed in a variety of dial plate colours, from deep blacks to silvers and whites, which would often be paired with contrasting, coloured chapter rings and sub-registers. More imaginative colours, such as salmon or electric blue, were also used. Roth also produced this reference with skeleton dials, showcasing the high level of finishing deployed in these watches.

You can find these chronographs in yellow, white and rose gold, as well as platinum – but no steel, unfortunately. It’s worth noting that the platinum examples appear to only have been produced with a black dial. Interestingly, these chronographs come up with both closed and display casebacks. Regardless of whether the caseback is closed or open, the quality of the movement finishing is identical.

The similarities continue when it comes to case design and the movements used.

Whilst the natural assumption might be that Roth began producing them with closed casebacks, then moved towards sapphire ones, we’ve not found any conclusive evidence to support this. For example, a watch numbered “77” – cased in yellow gold, with off-white pinstripe pattern – features an open caseback, whilst another one numbered “209” – cased in yellow gold, with a grey pinstripe pattern – features a closed one. Drawing a hypothesis in this area is complicated by the fact that Roth’s numbering system appears to count watches produced with a specific case and dial combination. As there are many different configurations out there, it’s difficult to assess where they sit in relation to one another in the production run. It’s more likely that the chronographs were offered with both a closed and sapphire caseback option.

The numbering of one Daniel Roth chronograph and the details noted on its paperwork.

Yet again, some rarer variations of the chronograph were also produced, namely a monopusher and split-second. The monopushers used a different Lemania ébauche, the 15CHT or 2220, which was originally designed in the 1930s. Due to the limited availability of the base calibres, these were limited to just 52 pieces, with 36 in yellow gold and 16 in platinum. Later on, after the watchmaker began to be less involved with the brand, 10 more of these movements were found and installed into Roth chronographs. These can be distinguished from the first batch of mono-pushers thanks to their swan neck regulator, which was not included the first time round.

A rare monopusher.

Not much is known about the split-second version, but it’s also understood that it was produced in the early 1990s. Early on in the decade, a batch of new-old-stock Venus 179 movements were discovered in a warehouse. These were divided between different brands, such as Ulysse Nardin, Girard-Perregaux and Paul Picot, who integrated them into a small number of wristwatches. Daniel Roth was amongst them, it is believed that the original batch only contained 10 pieces but 60 split-second chronographs using these movements were produced overall, all of which were reworked and finished to his standard.

A split-second chronograph from Roth and the Venus 179 movement that ran it.

There is some disagreement as to whether these were produced in the early 1990s, or later on, closer to the year 2000. According to a former Daniel Roth authorised retailer, split-second chronographs were still available for sale in the early 2000s. However, certain collectors speculate that the brand may have produced a second batch of these at this time, housing a non-original Venus 179 ébauche. A few years earlier, a watchmaker by the name of Jean-Pierre Jaquet is known to have produced such ébauches, which he allegedly assembled with a mix of fake and authentic parts. These were later sold to various brands, with some speculating that these may have ended-up in the second batch of Daniel Roth split-second chronographs. In 2002, following a series of crimes, Jacquet was arrested for robbery, receiving stolen goods, and counterfeiting of merchandise.

A platinum chronograph with the iconic pinstripe dial texture.

Before moving on, it’s worth noting that in 1996, the Daniel Roth brand began producing automatic chronographs powered by the Zenith El Primero movement. Beyond their mechanics, these can be distinguished by the fact that they have three registers, rather than two, as well as the date function at 4 o’clock. In the eyes of those who have focused on collecting the early pieces from the brand, these don't stand-up to the quality and aesthetics of the two-register, manually-wound chronographs.

The Rest of the Collection

Back to Simplicity with Time Only Models

As mentioned, the same year that Roth began production of his manually-wound chronograph, he also started to sell his first time-only model, the reference C107. Its design was very pared-back, with only an hour and minute hand. It also marked the watchmaker’s first attempt at making an automatic movement, which required moving away from the Lemania ébauches he’d previously used. This new model would hold a Frederic Piguet 71, one of the thinnest automatic calibres ever produced and another movement which Roth had used at Breguet. The off-centre rotor was originally designed by Frederic Piguet, in order to allow others to add modular complications on top of the movement. These were offered with both open and closed case back.

Strip away the complications and you’re left with great design.

The comparison with François-Paul Journe, in terms of how they both gradually built their collections, is an interesting one. Both started with the tourbillon. Both introduced another complication – the Résonance and the chronograph – paired with a convenient, everyday automatic watch – the Octa Réserve de Marche and the time-only C107. A year later, in 1991, Roth would release a manually-wound version of this automatic model, decreasing the thickness from 2.4mm, to just 1.73mm, with the reference C167. Again, he made use of a Frederic Piguet movement, though this time hidden behind a solid caseback. Roth also produced versions of this manual wind model with diamonds very early on, from 1990 to 1991.

Next is a model that really speaks to Roth’s inventive and playful approach to watchmaking: his retrograde time-only model, the reference C127. It was introduced at Baselworld in April 1991 and subsequently released in 1993. This model displays the time in a rather unusual way, believed to have been inspired by a pocket-watch made by none-other than Dr George Daniels. The hours are indicated on a fan-shaped display, with the hour hand jumping to the other side of the dial when it reaches 6 o’clock. This means that the hour hand never crosses the seconds dial. This model would see the return of Lemania, as Roth made use of the 27LN base calibre.

Roth’s retrogrades came in a range of combinations.

Once again, the reference C127 can be found in a wide-range of different configurations. The dials can feature both Roman or Arabic numerals, with two-tone and openwork dials have also appeared publicly. It’s believed that the Roman numerals are a feature of the earlier pieces, with Arabic numerals being introduced later on. Here again, Clous de Paris is found on some of the first pieces, with the pinstripe pattern believed to have arisen later on.

Rather interestingly, we also came across a two-tone case, combining rose and white gold. It appears that the bezel, crown and caseback are crafted from the white metal, with the middle of the case and lugs standing out in rose gold. This goes to show just how experimental Roth could be with some of his designs. To date, only a very small handful of two-tone pieces have been shared publicly, suggesting very few were made.

Many of the Roth Retrogrades which can be found on today’s market were produced from around 1995 onwards. These can easily be identified thanks to their large, bolder font used for the numerals and the Daniel Roth signature, as well as the lume which can often be found on the hands and numerals. The earlier examples are also likely to have a lower number, which will be printed on the dial, whereas the later examples have the number stamped on the solid caseback. Overall, to us, the early pieces seem closer to what Roth originally envisioned.

Developing the Perpetual Calendar with Philippe Dufour

Following the introduction of the Retrograde, Roth approached one of the most classic complications of horology, the perpetual calendar. Again, he kept this model very close, aesthetically, to the rest of his current collection, keeping the metal chapter rings and sub-dial at six o’clock. The sub-dial is used to indicate the date on the periphery and the year on the inside. As for the month and day of the week, these were either shown on apertures above this sub-dial, or two smaller sub-dials which overlapped with the hour and minute track. A rather compact way of displaying all the information a perpetual calendar needs to convey. The series number was also moved to the edge of the caseback.

A catalogue from 1992 showing the two different dial layouts for Roth’s Perpetual calendar, courtesy of @ciaca70.

This model, the reference C117, was developed in collaboration with another famed independent watchmaker who had only just got off the ground a year earlier, Philippe Dufour. Having recently announced his decision to become independent at Baselworld in 1992, which is where he displayed his impressive Grand Sonnerie wristwatch, Dufour must have seemed like the obvious choice. He was a highly skilled watchmaker looking for work and happened to live just down the road from Roth. As their foundation, the pair used a Lemania ébauche once again, this time the 8810, which they worked into the double-ellipse case.

The two different dial layouts of the Daniel Roth perpetual calendar.

Dufour tells us that it wasn’t easy, even for someone of his skill, “I remember it being hard work. It took me about six or seven months to finish the movement.” Of course, this wasn’t just any normal perpetual calendar. Roth and Dufour were attempting to make a world’s first instantaneous perpetual calendar, where all the indicators would instantly flick over at midnight. Evidence suggests that Roth had announced his intention to bring this design to life at Baselworld in 1991, where he presented a prototype featuring the apertures for the day and date. However, as Roth and Dufour quickly found-out, too much energy was required for all the indicators to jump over at midnight. As such, they replaced the digital display with two sub-dials for the day and date, in order to decrease the force needed to move all the gears.

The different types of movement rotors that were used for the perpetual calendar.

Since the project had initially been presented with a digital display, it is understood that both versions were released at Baselworld in 1993 – two years after the project was first announced. On the one with the apertures, the day and date slowly transition at midnight, rather than jumping instantaneously. This is the one that Roth and Dufour struggled with, ultimately failing in their goal.

The one with the sub-dials, however, is understood to instantly flick over at midnight, making this one a true instantaneous perpetual calendar. Though it might seem like a subtle difference between the two designs, behind it lies the horological struggle of two of the finest watchmakers of their day. “When it first came out,” Dufour remembers, “they never mentioned the fact that it was instantaneous, they never do.”

To identify these original perpetual calendar models, one just needs to look at the movement. The early ones are powered by the Lemania 8810, whereas from around 1995, the brand transitioned to using the Girard-Perregaux calibre 3000. One instant giveaway of the difference is that the early ones had a full gold rotor, where later examples have a platinum and gold rotor. This is a rather important detail as some of the later perpetual calendars can look deceptively similar to the early ones powered by the movement developed by Roth and Dufour.

The Final Models

A few years later, in 1995, Roth brought out one of his most elusive models, the minute repeater. Unlike his other complications to date, this would not be a regular production piece. It is believed that only three of these were ever made, one in each colour of gold – yellow, rose and white – and they are rarely seen in public. Roth again made use of a Lemania base, specifically the 389.

Roth’s minute repeaters are hard to come by, courtesy of Claudio Proietti of Maxima Gallery.

From 1995 onwards, with Roth being less involved in general strategy and model conceptualisation, the focus of the brand changes radically. This can clearly be seen in some of the models which were released at this point, from the automatic chronographs to the various reinterpretations of his first models, many of which looked to further modernise his original aesthetic.

The Papillon helped celebrate 10 years of Roth’s eponymous brand.

However, one model stands out from the period which followed 1995 – the Papillon. Introduced in 1999, it was released to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the brand, with Daniel Roth himself getting involved in the model’s design, once again. This distinctive jumping hour, retrograde model with its sweeping metal inserts on the dial, takes its name from the French word for butterfly. It was produced as a limited edition of only 250 pieces – 110 in white gold, 110 in rose gold and 30 in platinum. Some watches were made under the Papillon name following the sale to Bulgari in 2000, but these are quite different. All of them would have been made after Roth’s departure in 2001, and they were still in production into the 2010s.

Daniel Roth Today

Roth working away in the attic workshop above his house in Le Sentier. Shot by Fred Merz for FHH Journal.

As we’ve previously mentioned, since leaving the brand, following its sale to Bulgari, Daniel Roth no longer works under his own name. He is, however, still making watches, under the name of Jean Daniel Nicolas – a combination of his son’s name, Jean, his own name and that of his wife, Nicolas. All three of them are involved in the business, making this a family endeavour. His wife, a watchmaker herself, assists Roth wherever she can. Meanwhile, his son is apprenticing under his father. Starting a completely new venture at the age of fifty-five was no small task, however, without the pressure of marketing departments and a board of directors to contend with, Roth seems able to produce some of his finest work to date.

Roth now works in two case shapes, a classical round and a separate curiously shaped case.

They produce roughly three watches a year, all of which are bespoke commissions based around a tourbillon of Roth’s own design. With the watchmaker now well into his seventies, the waiting list for new Jean Daniels Nicolas pieces has closed, with only a select few of those already made coming up on the open market. We see it as rather fitting that, today, Roth dedicates his time to making tourbillons – a complication invented by Breguet, a name he helped bring back from the dead, and the foundation on which he first built his eponymous brand.

Our thanks to @ciaca70, Claudio Proietti, William Massena and Philippe Dufour for sharing their insights, memories and recollections of Daniel Roth the man and the brand. We would also like to thank @ciaca70, Baruch Coutts and Richard Meng for supplying some additional imagery and early pieces to be photographed.