The Morteau Makers: Rémy Cools

Kwan Ann Tan

Rémy Cools intends on carrying the torch for French watchmaking. Single-minded in the pursuit of his vision, Cools’ story is one of determination and a strong sense of his place in history.

Currently located around Annecy, France, Cools’s workshop makes around 12 watches a year with only two watchmakers at work – himself and his partner. Despite this, the work continues at an unrelenting pace, as his inaugural Tourbillon Souscription pieces have just been completed, with the Tourbillon Atelier having been recently announced.

In this interview, we spoke to Cools about how his school years helped him develop his work ethic, how history has shaped his watchmaking vision, and why craft is at the forefront of his practice.

ACM: What was your first impression of watchmaking as a child, and what made you decide you wanted to be a watchmaker?

Rémy Cools: I don’t come from a watchmaking background – no one in my family works in watchmaking. But one Saturday, my father brought me to a watchmaking facility.

When I got into the factory, it was a totally new discovery for me. One of the watchmakers told me that I could go to the bench and try to do something. This was a complete revelation. When I went home, I told my parents, “OK, I really want to become a watchmaker.”

Do you remember what you were feeling when you first spoke to those watchmakers?

Yes, it was really almost instant, my focus on the work. I was about 11 years old at the time; the watchmaker took about half an hour to explain to me how a mechanical watch worked, and I remembered a few things about it, but I was totally absorbed, especially when I got to sit at the workbench.

After that, you decided to attend the Lycée Edgar Faure?

Yeah, this was one of the most famous watchmaking schools in France, and it was really close to my parents’ house, making it the most logical choice.

Do you feel that your time at the school has shaped your style today?

It was great to get all the basics of watchmaking from my studies in Morteau. But I think I really shaped my watchmaking vision after school, because I had a one-room apartment where I was able to set up a tiny workshop with one workbench and one cleaning machine where I could do some restoration and servicing for Swiss and French collectors.

So, after school, I would come back to my apartment, where I would clean these watches, repair them, etc. It was really intense. But it was also great for me because I quickly learned how to be reliable, how to do something quickly and well, and I also got the opportunity to look inside different kinds of watches and clocks, including marine chronometers and pocket watches. It taught me how to appreciate all the styles of the original machines.

It must have been quite difficult to juggle your studies and restoration work.

It was a really hard time. You know, you come back from school really tired one day, but you have to deliver a piece to a client, to do some cleaning or restoration. It shaped me – not in terms of work routine, but to be very reliable.

How did you meet your clients in the first place?

I often visited flea markets and collectors fairs and there I met antique dealers, or people who needed watchmakers to repair or clean their watches and clocks. I said OK, I can do that.

Were there any instructors that you particularly admired during your time at school?

I personally think it’s not the teacher who shapes the student. If you aren’t a smart student, you just do the things that the teacher tells you to do. But you need to go beyond that, to find the solution and reflect on how you can adapt the solution to your work to improve it.

So school was great for basic skills and simple things, but if you want to go deeper into other watchmaking facets, you have to be smart, you have to do it yourself, [and] you have to be independent.

When did you realise that you had to be an independent student?

Since the beginning. For example, normally on Wednesday afternoons the school is closed, but I asked my teachers if they could open the workshop for me to do some work. I was almost full-time in the workshop. You can’t learn a job correctly if you are not 100%, fully within it.

After you graduated, what was the big push for you to become an independent watchmaker?

After I graduated, I did have the idea in my mind to set up my workshop directly after finishing school. But I said, OK, I’ll go into a factory or workshop first, before I see if I can actually set up my own place. After three months, I said OK, I can manage it – I’ll start my own workshop.

What has the journey been like so far?

Very complex. When you start from zero, you have to learn a lot. I’m still learning every day, and it’s really interesting. There are different problems and different solutions, and I am evolving all the time.

For example, with my first Souscription series, it was really quite raw. Not in the sense that it was bad, or there was bad finishing or bad design and development, but with the new one I was able to learn from my first experience, and it shaped my design, so that it’s thinner and more elegant.

You know when you create something, you want to push the quality you can achieve and take it to the next level with every creation. [I’d] been working alone for the first three years, and I have had one watchmaker helping me for the last two years. It’s important to me to find the right people to work with me because it’s not a normal watchmaker job – our quality is very high, so it takes quite a long time to train the watchmakers in the workshop. But this is important for me too, to perpetuate and train people.

What’s been the most challenging part to date?

I’m the first in my family to set up my own business, so I didn’t really have anyone to ask for advice. Although it’s a watchmaking workshop, this is a business too. You have to learn all the administrative things and create at the same time. You have to separate your brain into two parts – one part is the artist, and the other part deals with business. You also have to set up all of the machines, the entire control process. You have to set up every step of the manufacturing of the watch.

I learned a lot from the process, from every step [such as] finishing, quality control, accuracy, making the parts, and talking to people. We work on every aspect of the watch from A to Z. At the moment, we have a few suppliers who make some parts for us, but my goal in the near future is to be totally independent in terms of everything.

It seems like a huge job just for two people.

Yes, it is. Some collectors and clients take the time to visit the workshop sometimes, and when they see all our machines, all of the hard work it takes to make a watch, they say “OK, I understand how much goes into it now.”

Historical inspiration, creative iteration, and completed examples.

Where do you begin when you’re designing a new watch?

I first draw the dial of the watch, because it’s the most important thing. After that, I adapt the mechanics to the design. I always carry a little book with me so that when I get an idea, I can quickly make a note or draw something. Sometimes it’s just like a flash, because I see something and think I can do that, but sometimes you gather a few details together and say OK, I can do something cool with this. Then it becomes the next creation.

For example, with your Souscription pieces – how long was that idea in the works?

I think I took one year to develop the Souscription, in terms of just developing the concept, designing the dial. After that, you move to 3-D construction on the computer, and sometimes you have to change things a little bit because there are mechanical issues. Little by little, you work to match the mechanical and design sides perfectly.

Why choose to use the Souscription model for your first watch?

The subscription model is a very old process in watchmaking, and it was used by [Abraham-Louis] Breguet to set up his workshop in Paris after the French Revolution. Of course, [F.P.] Journe did it in the 90s with his first tourbillon watches as well. For me, it just made sense when I was starting out.

Was the process of creating and delivering them challenging?

Yeah, it was a total learning curve over those two years because it was my first production. It was a lot of learning about process, quality control, the manufacturing process… and you have to learn very fast. Very, very fast.

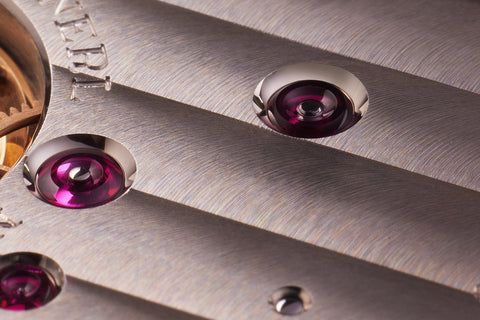

The tourbillon has featured heavily in all your work so far. Why choose this complication?

I think this is one of the most beautiful complications in watchmaking, because it’s really like a living thing. You can see this little heart beating and telling you the time. It’s really a demonstration of the watchmaker’s skills.

What does traditional French watchmaking mean to you?

For me, it’s a kind of heritage. We have such a beautiful history of watchmaking in France, over 400 years of making clocks, pocket watches, and wristwatches.

When you’re fascinated by your job, you are really touched by the story, and this history really inspired me. I think it’s great that we have more people being inspired by French watchmaking. The last great French watchmaker was around the end of the 19th century, and so we have a new start, with my generation, to continue the legacy of these masters – at least, we are trying!

Making a watch is incredibly complex and making all of the components, even with our new methods and new machines, is still difficult. So it’s really humbling to think about how so many historical watchmakers worked without electricity, without anything.

Is there a specific design feature on your watches inspired by traditional French watchmaking?

I wanted my watches to continue the legacy of French watchmaking, so I asked myself, when you handle your pocket watch, or clock, or chronometer, what do you want? At the time, the designs were really simple, and I really like simplicity in terms of aesthetic and mechanical things, because it’s really difficult to pull off. Everything has to be very clean and perfect, and there is no room for mistakes.

For example, the design of my balance wheel was inspired by a chronometer balance wheel from the middle of the 18th or 19th century. It’s similar to those found in traditional clocks or pocket watches. I want to continue this legacy and perpetuate this style of French watchmaking, but I also don’t want to just make a copy. If you compare my watch with an older pocket watch, you can definitely see a family resemblance, but it’s not just a copy. That’s very important to me.

Why do you think it’s important to modernise these traditional styles?

It’s not my goal to make a 200-year-old pocket watch in an older style. I like the current period I live in, so I take all the spirit of history, but adapt it for my time.

You also collect a lot of vintage machinery, which you use to help create some of your watches. What has that process been like?

I started collecting machines as a student, and it’s not really a collection, it’s the actual tools that are part of the job. I have a mixture of new and old machines, because old machines can sometimes be more accurate and reliable compared to a new machine. I also really like the spirit of the old machines, it feels like the same spirit in the work of the old masters – reliable and precise.

Is it difficult to track down these pieces?

I bought my machines just a few months after I started my workshop, [which is] about 10 years old now. You can’t really set up a workshop full of old machines in one month – it’s not possible. Sometimes it takes me two or three years to find the right machine. So it’s really both long-term patience and a long-term vision.

Would your childhood self be happy to see how far you’ve got today?

Yes, of course. I’m really happy with my situation at the moment. I hope to evolve in the next year, but you know, winning the GPHG [Le Grand Prix d'Horlogerie de Genève] award was an incredible achievement for me.

Do you have a vision for the future?

We have many different projects in the works for the next 10 years. Many exciting things; many different watches. When I think about the future, I imagine having a small team of really great, intelligent people, to expand production. My goal is to produce between 30 to 50 pieces a year, and I really want to keep my work exclusive.

My real goal is to bring back French excellence in watchmaking, and to set up a workshop in the same style as those from 200 years ago, with all of the different machines for decoration, people and watchmakers, but not in an industrial way – more of an artisanal way of craft and creation.

Our thanks to Rémy Cools for bringing us into his world and speaking to us about his craft.