From the bench: Max Busser

A Collected Man

True originality is something of a scarce notion in the modern watch world, with copycat brands, regularly borrowing from the successes of others. One brand that can quite comfortably be described as ‘original’ is MB&F, with their weird and wonderful horological creations, ranging from mechanical music machines, to wristwatches and clocks. MB&F is the brainchild of Max Büsser, who made his mark with brands like Jaeger-LeCoultre and Harry Winston. We flew out to Geneva to spend some time with Max, to get a better understanding of who he is and how the brand came to be.

Let’s start right at the very beginning. What were you like as a child?

I was very lonely as a child. I was the kid who didn’t fit in and I remember actively looking to make friends, but I didn’t make many. I felt different to everyone else, which is really bad when you’re a kid, you don’t want to be different, you want to be like everybody else. My bedroom was as much my prison as it was my kingdom, I was so often in it, alone. What I thought was a pretty unhappy childhood lead to a fantastic adulthood and I think MB&F owes a lot to that.

So what would you be doing to entertain yourself?

My imagination would be running wild, my imaginary life was my security-net, keeping me from going nuts or getting depressed. In my kingdom, I was a full-time superhero, saving the planet. I was captain Kirk, Han Solo or Luke Skywalker depending on my mood. It’s kind of interesting, because years later, I still have this instinct in me, to save people who are in difficulty. I think that gave me a lot of empathy, which is now very deeply rooted in me.

You recognise the things in others that you suffered with specifically?

Yes, I think because I have suffered, I feel for those who suffer. Today at 50 years of age, I’m pretty evenly tempered, but if I see someone doing something that I believe is fundamentally unfair, then I become Godzilla.

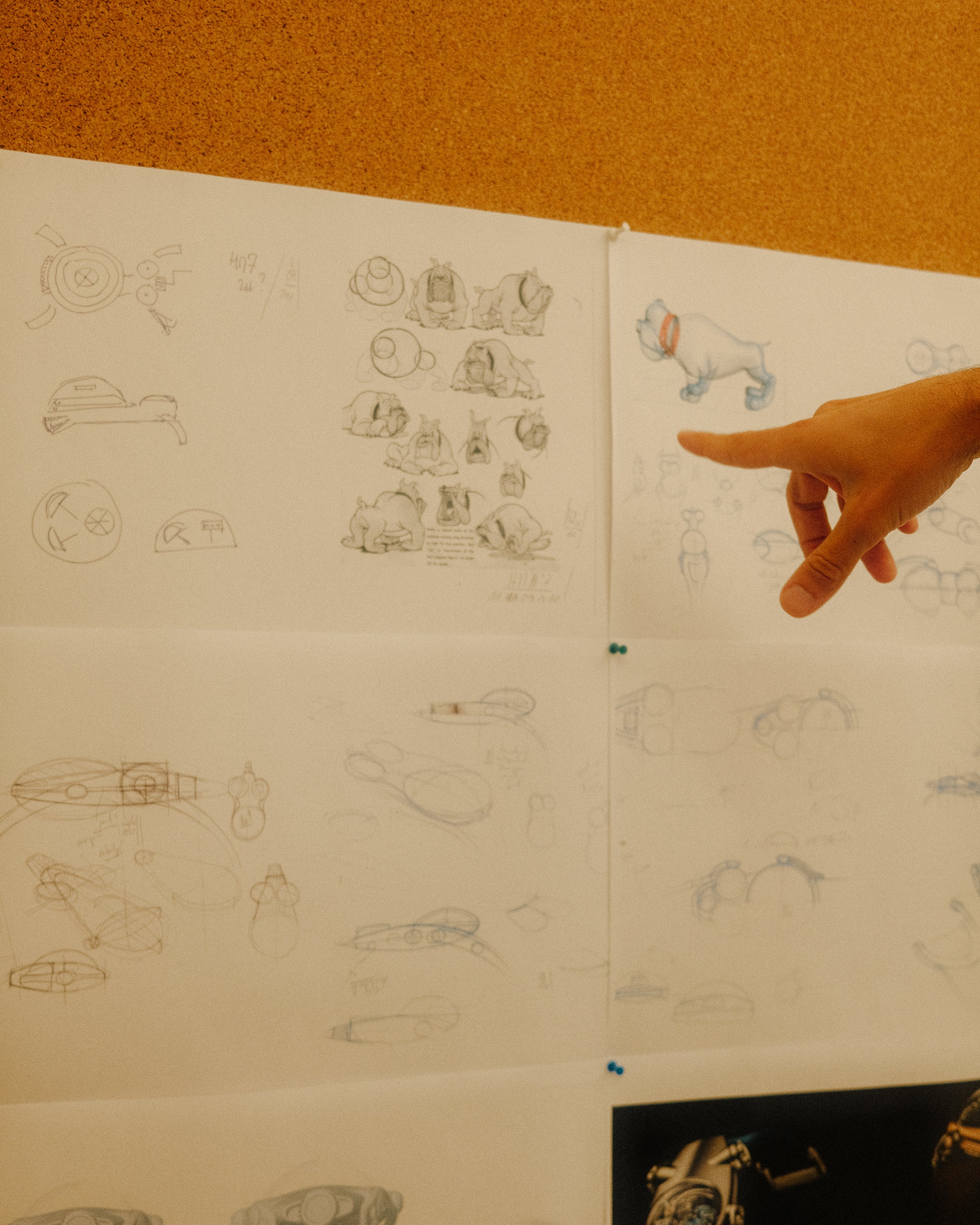

Did your imagination manifest physically when you were a kid?

Oh yes, from the age of four until I was eighteen, I was a full-time car designer [laughs]. I would draw cars constantly, and where most boys would cease to do this kind of thing around the early teenage years, after discovering girls, I continued designing. My biggest dream was to become a car designer.

What were the designs like?

They were completely varied, but I was a big fan of Luigi Colani, who is credited with having launched bio-design with all these amazingly organic looking shapes, when everyone else was designing wedges. You see these more organic shapes more frequently today, and this inspiration definitely had an impact on the design at MB&F, like in the HM Space Pirate for instance. It’s something I didn’t allow myself to draw-upon in the early days of the brand, but now it flows throughout the brand’s design identity.

The MB&F workshop in Geneva, Switzerland.

Speaking of watches, do you recall any early encounters with watches?

Absolutely not. Well, actually that’s not true. There is one very important routine when I was young, which was winding my manually-wound Jean Perret watch with my father. I don’t even know if the brand continues to exist today, but, during a time where fathers didn’t communicate much with their offspring, we had a special, nightly-routine where he would come to wish me goodnight, and I would always wind my little watch.

That’s a nice routine to have as a child…

Yes, and then later, when I was eighteen, my parents told me that they would like to buy me a watch for my birthday, like most parents do in Switzerland. I was eighteen in 1985, and at this time mechanical watches were dead, it was all quartz, quartz, quartz. I had been given a budget of 700 Swiss Francs, and the task of finding a watch that I would like. This was an enormous amount of money for both my parents and myself, so I begin looking at watches, and I end up sitting next to a random person on a bench at my university, who was wearing a watch. I asked him what it was, and he replied with, “It’s a Rolex”, So I asked, "What’s a Rolex?”.

"He started to explain to me what it was and told me that it was mechanical, at which point I said, “woah, woah, woah, back up, it’s mechanical?”. I continued to say, “Why on earth would anyone want a mechanical watch, it’s antiquated technology”.

[Laughs] Ok…

He started to explain to me what it was and told me that it was mechanical, at which point I said, “woah, woah, woah, back up, it’s mechanical?”. I continued to say, “Why on earth would anyone want a mechanical watch, it’s antiquated technology”. I remember towards the end of our conversation, I asked him how much it was, and keep in mind that my budget was 700 Francs and he told me it was 4700 Francs. I gave this poor guy absolute hell, telling him that he was completely bonkers to have spent that money on old technology. That’s when my curiosity started, because I just couldn’t understand why someone would be nuts enough to spend that kind of money on a mechanical watch. In fact, that’s the first time I can remember being interested in that as a subject.

What was it that you found so difficult to understand exactly?

Well, the guy was very elegant, clearly from a good family, and it just intrigued me that someone who had such good taste would wear something like that.

What watch did you end up buying for your 18th birthday?

After all that, I went and bought a quartz Tissot.

And did you ever get to the bottom of why someone would spend that much on a mechanical watch?

Well, two years later during my engineering course, I had the opportunity to write a thesis on a subject of my choosing, and I decided to write about this. My thesis was called, ‘why the hell would anyone spend this amount of money on a mechanical watch’. [laughs] Not really, but it may as well have been. I sent letters, hand-typed because we used to send letters in my day, [laughs] to all the different brands saying, “Hello, I’m a student and I’m doing my thesis on this, and would you have some time to explain it to me?”.

What brands did you send this to?

Vacheron Constantin, Jaeger LeCoultre, Audemars Piguet, Breguet, Gerald Genta and Patek Philippe.

And did you hear back from any of them?

Yes, all but one. Patek didn’t have any time to give me, but each and every other brand replied, and in all cases, to my surprise, it was the CEO who responded.

What did they say?

Well, they told me they could give me x amount of time on such and such date, and so on those dates, off I went with my little briefcase to interview the various CEOs. They more or less all told me the same thing, which was that they were aware of the fact that what they did made no practical-sense, but that it was just so beautiful that it needed to be kept alive. They explained that the industry was made-up of artisans and craftsmen with skills that would disappear forever, if they didn’t keep it going. It was the first time I had heard the word beauty associated with engineering, these people were talking about history, about legacy and this was just so appealing to me. In those days, engineering was a particularly dry subject to study, consisting of you and your computer solving equations. Humans seemed like they were a liability in the process and needed to be taken out of it [laughs].

"It was the first time I had heard the word beauty associated with engineering, these people were talking about history, about legacy and this was just so appealing to me."

So these meetings completely changed your outlook on the topic…

Yes, that was when I became completely hooked. Somebody was talking about humanity and engineering and it made so much sense to me.

Then how did that curiosity develop?

The passion for the watch industry continued to develop over the years, but then, when I was 22 I had a horrible accident in the army, and I should not have survived. There is absolutely no reason whatsoever that I survived it. I spent six weeks in hospital, and when I got out, with my entire torso in plaster, I jumped on a bus to Lausanne to buy myself a watch to celebrate the mere fact that I was still alive and breathing.

Some of the artwork found in the foyer of the workshop, a functioning openworked wall clock and a windmill-esque sculpture.

Seems like a good reason to buy a watch. What did you buy?

I bought my first real mechanical watch and that was to be an Ebel chronograph which featured the same Zenith El Primero movement that the Rolex Daytona used. But we’re talking about the late 1980s, Ebel was a much sexier brand than Rolex at the time. So I bought the watch, which cost me 2,750 Francs, which I remember down to the last Franc because it was such an enormous sum to me at the time. I basically emptied my bank account to buy that thing, and people did the same thing I did to the Rolex chap that I met, saying things like "Are you crazy?”, “You spent how-much on a mechanical watch?!”.

How did you then find yourself working in the watch industry?

It was an incredible story of fate because I had decided that I no longer wanted to be an engineer, and applied for a job with Nestlé and with Procter & Gamble and it was in the middle of multiple rounds of interviews when I bumped into the then Managing Director of Jaeger LeCoultre on a skiing trip in 1991. We recognised one another from when I had visited the headquarters previously, and we sat-down to have a coffee and catch-up. He asked me what I was planning on doing with my life and I filled him in, telling him that I was interviewing at these big firms, and I said half-jokingly that if that fell-through, that maybe he could give me a job at Jaeger. He laughed, I laughed, then a week later I was called to see if I would come to the Vallée-de-Joux to meet with the Mr Belmont. I said, “absolutely” and I hopped into my beaten-up Opel Corsa, which in the UK would probably be a Vauxhall Nova right?

Indeed it would…

So I drive up to the Vallée-de-Joux to the job interview of a lifetime. For three straight hours, Mr Belmont sold me his dream for Jaeger LeCoultre, how he was planning on saving the brand, what he wanted to change, showing me the collection. He barely asked me a single question, telling me that he needed a young engineer who loves watches to come and help this dream become a reality. He said that he wanted to create a job for me there, which would be to become the product manager of the brand.

Wow…

Yeah, I’m like, sorry what?

Then what happened?

I told him that I was in the third interviewing stage at Nestlé and would need to come back to him once that had concluded. He said I could have three weeks to decide, which I immediately told him that I would need much more time than that. He responded with, “No, I’m giving you three weeks, because you have to know one thing in life, do you want to be one, amongst two-hundred-thousand people within a corporation? Or do you want to be among the three or four people who save Jaeger-LeCoultre?”. That was exactly what he said to me, and I said, "Ok thank you very much" and left. I called him the following morning and said, let's do this. It was the first decision I think I ever made with my gut and not my brain.

You weren’t much of a risk-taker generally speaking?

No, I was a very cerebral child, to protect myself. I was very intellectually-intense and every decision was thought-out very carefully. Everyone thought I was nuts for accepting the job, asking me why I was taking a job with a half-bankrupt little watch company rather than the global institution that is P&G. I told them all that yes, I probably was crazy, but Mr Belmont believed in me much more than I believed in myself, and I owe a great deal to him.

What do you think he saw in you?

I don’t know really, you’d have to ask him. Looking back, I was always very intense and I only realise that now. When I was passionate about something, I was really passionate about it, which is often something you see in children without siblings. I don’t think he had ever met a youngster of that age in that era who was so passionate about watches. There are loads now, but then, there were hardly any.

Do you think he was just trying to surround himself with the ‘right people’?

Yeah, and I think it was tough for him to hire people, because in the years that followed, we did the exact same thing as he did to me, when hiring. We would sell the dream in order to get these talented individuals to work for us. It’s a strange thing to be in that position, where you’re interviewing candidates, but it’s more like you’re trying to persuade them to work for you.

"None of us were great at what we did individually, in fact, virtually nobody from Jaeger has become one of the great leaders of the industry, but together, we were an unbeatable team."

What did you learn working with Jaeger?

I learned watchmaking, and I mean hardcore watchmaking. But I also learned the basic principle that it’s all about great product. We were utterly useless at marketing and communication, so we had to make great product. I also learned how to work there, because I was straight out of college, so it taught me certain, necessary disciplines. I learned that a great company relies on a group of individuals and cannot rely solely on individual competence. None of us were great at what we did individually, in fact, virtually nobody from Jaeger has become one of the great leaders of the industry, but together, we were an unbeatable team. We shared the same inspiration and the same desire to save the company.

What exactly was the problem with the brand in your opinion?

I don’t think there was anything particularly ‘wrong’ about it, but more that people just didn’t know the brand. We were doing such small revenues at the time, I mean, when I joined we were only doing CHF 17,000,000. Seventeen. One seven. That’s more or less what I do at MB&F today, but we had 220 employees, and a factory creating absolutely everything ourselves. We were making far more money selling our movements to third party brands than we were selling our own.

What sorts of brand were you supplying to?

IWC, Breguet, Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet. They all used our movements, but no customer wanted to buy a Jaeger-LeCoultre. The Reverso was coming back slowly, I mean, I remember out of however many thousand watches we were producing, the Reverso represented less than 10% of our revenue. Even the best retailers in the world were saying to me, “Young man, this watch which turns over makes no sense, why are you manufacturing this?”

Incredible to think how much that has changed for that piece…

It seems utterly surreal to hear something like that today. I feel like a dinosaur thinking about all this. [laughs]

So, tell me about how you first got the idea to start a brand of your own…

It became clear to me that at the age of 35, I needed to write my own story, but at this time, I didn’t know how to do that and certainly didn’t have the means to. I started to sketch what would become the HM1 back in 2003 while on a flight back from Singapore to Geneva. I managed to get the shape of the watch and what I had initially planned to call the company on there.

The plan wasn’t always to be MB&F?

Well, no, initially I had planned on calling it B&F, but my trademark attorney informed me that Bell & Ross would likely block us if we were to go with that.

Not an ideal potential issue to deal with as a new company…

No, certainly not. So I added the M, to become MB&F, even though everyone told me that was the worst name ever for a watch brand. I began relentlessly sketching and developing other ideas, while simultaneously developing Harry Winston timepieces. The more and more the concept developed, which, let’s be honest, was economical suicide and completely insane, the more I fell in love with the idea and decided to take the plunge after Baselworld in 2005.

How were those early days?

Well, I had saved CHF 900,000 over my seven years with Harry Winston, which may seem like a lot of money, but it was a drop in the ocean when you’re talking about launching a high-end mechanical watch brand. I had spent weeks populating a profit and loss spreadsheet, and realised that the absolute minimum investment required to get this thing going was 1.6 million Swiss Francs.

Yikes, so what did you do?

Well there was no chance that I was going to let any financial shareholders into my company, so one day, I had a crazy idea; I thought, what if I could get the remaining 700,000 Francs by pre-selling 25 HM1s and get the retailers to pay me a 35% advance on those orders, two years ahead of delivery.

The ballroom space of the original house has since been converted into the main bulk of the workshop, where the magic happens (left). An example of the HM10 Bulldog (right).

Did it work?

While travelling around the world over a period of three weeks I tried to convince retailers to follow me on my nutty idea. Amazingly, five of them agreed, which were Chronopassion, Westime, The Hour Glass, Seddiqi and Ghadah. Thinking back on it, I shudder because I had absolutely no backup plan. We ran into some serious difficulty when STT, the company which I had hired to engineer, manufacture and assemble the movements for the HM1, was sold very hastily in 2006. The brand who had acquired STT clearly had no interest in supplying products to third parties, and so the months following that brought MB&F incredibly close to bankruptcy.

So the concept for the brand is based around collaboration, what is it about collaboration that you found appealing?

I have only two talents, if that. I think differently from most people, and I have an ability to gather great people to work with me. After many years, I started to understand this more and more, and so that became the basis for MB&F.

"I have only two talents, if that. I think differently from most people, and I have an ability to gather great people to work with me."

How does the process work?

Creatively speaking, I do my best to be an enlightened dictator [laughs].

[laughs] Ok…

I have some very clear ideas and listen to my team's feedback along the way, but the end decision is always mine. Creativity is not a democratic process, particularly if you’re looking to explore unchartered territories.

Do you ever run into friction under this type of structure?

We’ve had our fair share of disillusions with people we have worked with over our twelve years, as true integrity is actually pretty rare in the Swiss watch industry. You know, at the inception of the brand, I had stated that we would never integrate manufacturing within the company, and now we have three, 5-axis CNC machines which we use for machining components and we are even starting to manufacture some of our own cases; this is out of necessity, not because we have chosen to.

How was the collaboration with Kari Voutilainen on the now very recognisable ‘balance wheel on the dial’ models?

Working with Kari is one of the many standout highlights of my twelve years, and I will always remember the first time I tried to enrol him into the Legacy Machine project.

How did you convince him?

Jean-François Mojon and Serge Kriknoff and I drove up to Kari’s workshop and I explained, with a little nervousness, that I was working on a project which would pay tribute to 19th century watchmaking and that we would be honoured to work with him on the project.

How did he respond?

He carefully listened to everything we had to say, but politely declined, saying that he would love to do it but that he had far too much on his plate to accept. It was a complete disaster.

The LM Perpetual EVO in a vibrant red colourway (left). A watchmaker fine-tuning and adjusting one of their movements (right).

So what did you do?

I immediately pulled an early design of the LM1 out of my bag and put it in front of him, asking maybe if he had some advice for us. Kari stared at the design and began making suggestions like, “wouldn’t it be great if the balance were a little more like this, and if the bridges were like that”. He didn’t stop drawing and developing the thing for the best part of three or four minutes, during which we were silent and listening. He stopped, looked up at us and I dared to ask one last time, “does this mean you will work with us on this project?”, he smiled and said, “on this project, of course.” The rest is history.

Wow, that’s amazing. Did you ever regret any of the machines you’ve made?

I never let a machine come out of the workshop if I'm not proud of it. This doesn’t mean they were all successes or understood correctly. Take the HM5 ‘on the road again’ for instance, this was an extremely difficult project as much emotionally as it was technically. The mirror system was a complete nightmare to develop and we took many paths before finding a solution. It would be fair to call his our biggest commercial failure as we only produced and sold 130 of the intended 198 pieces, and we were unfortunately unable to amortise our R&D costs.

Does that play a big role in what you make, the physical possibility of things?

Of course, many of the initial ideas need modification because of engineering constraints. But you know what they say, no pain, no gain.

[laughs] Very true…

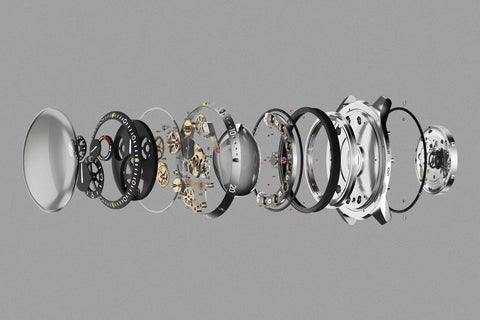

It’s part of the deal, and for some of our ideas, we are yet to find the expertise to transform them into reliable realities. Reliability is a very important factor for us. Ask any retailer and they will tell you that the brand has among the best quality track-record across the market. We have developed fourteen calibers in twelve years, and our commitment to reliability has allowed us to come so far.

"Creativity is an addiction and the dosage needs to be increased all the time, otherwise you don’t feel much of anything anymore."

The unusual MB&F cases are created in the workshop itself.

On a final note, what can we expect from you guys in the coming years?

A hell of a lot. [laughs]

We’d expect no less…

Creativity is an addiction and the dosage needs to be increased all the time, otherwise you don’t feel much of anything anymore. Having said that, I decided in 2013 when we hit approximately 15 million Swiss Francs in annual revenue with fifteen employees, that the company would not grow from there. We need to create within our means, and our R&D budgets cannot be increased. We need to maximise within these constraints to get all of our new ideas out there.

We thank Max Busser for welcoming us into his workshop in Geneva and answering our many questions.

Photography by Benoît Chow.