Menu

A Collectors' Guide to Urwerk : Part One

October 2024

• 30 min read

A Collectors' Guide to Urwerk : Part Two

October 2024

• 20 min read

A Collector’s Guide: Early F.P. Journe, Chapter One

May 2020

• 22 min read

A Collector's Guide: The Datograph

December 2021

• 21 min read

Collectors Guide - Early Daniel Roth

February 2021

• 20min read

A Collector’s Guide: Parmigiani Fleurier

December 2022

• 20 min read

A Collectors Guide: The Patek Philippe 3940

April 2020

• 22min read

Sylvain Pinaud - Origine

September 2024

MB&F - Pre-Owned Approved Partnership

July 2024

Raúl Pagès - RP1

March 2024

Winnerl - Tremblage

July 2023

Petermann Bédat - Reference 2941

March 2023

Roger W. Smith Series 1 - Unique Piece

November 2022

Baltic - MR01 Blue Roulette

September 2022

Rexhep Rexhepi - CC II

May 2022

A. Lange & Söhne

A. Lange & Söhne was originally founded in 1845 in the town of Glashütte as a pocket watch manufacturer but was only truly revived in the early ‘90s. Famed for the architecture and exquisite finishing of their movements, even Philippe Dufour himself once stated that A. Lange & Söhne makes the best chronographs in the world.

AKRIVIA & Rexhep Rexhepi

AKRIVIA was established in 2012 by brilliant young watchmaker Rexhep Rexhepi. Having started his horological career at the tender age of fourteen, on graduating, he went on to lead the complications team at the movement manufacturer, BNB Concept. Learn more

Andersen Genève

Svend Andersen worked at Gübelin and the Patek Philippe complications department before striking out on his own in 1980 to start Andersen Genève. Notably, Andersen is also the co-founder of the AHCI alongside Vincent Calabrese, an organisation celebrated for their championing of independent watchmakers. As a brand, Andersen Genève has focused on developing complications, and are well known for allowing collectors to personalise and create truly unique watches.

Andreas Strehler

Andreas Strehler began his career in 1991 as the head of prototyping at Renaud et Papi, a Swiss movement manufacture where many of today’s most celebrated independent watchmakers cut their teeth. In 1995, he opened his own restoration workshop, then released his first watch, the Tischkalender, in 1998. Strehler is perhaps best known for his behind-the-scenes work as a movement developer for numerous brands and projects within the industry, with his own watches displaying incredible ingenuity and unconventional style.

Armin Strom

The brand was initially conceived by Armin Strom in 1967, who became known for his skill in the hand-skeletonisation of watches, which continued over the next 30 years. In 2006, he passed the brand over to founder Serge Michel and watchmaker Claude Greisler, who continue to helm the manufacture today, continuing Strom’s legacy but also focusing on bringing its Swiss-German heritage into the modern era.

Atelier De Chronométrie

Hailing from Barcelona, Atelier de Chronométrie is composed of several collaborators, and is a rising star in the field of independent watchmaking. Their creations draw inspiration from coveted mid-century pieces of the past, with a distinctly modern twist. The workshop is especially famous for its handmade approach, and they produce bespoke pieces in highly limited numbers, capturing the elegance of a golden age of watchmaking.

Audemars Piguet

In 1875, Jules Louis Audemars and Edward Auguste Piguet founded the watchmaking manufacture Audemars Piguet in Le Brassus, Vallée de Joux. Since then, the brand has become synonymous with aesthetic refinement, mechanical craft and historic lineage. Though Audemars Piguet is probably most widely recognised for introducing the Royal Oak in 1972, their contribution to watchmaking is far greater.

Auffret Paris

Auffret is part of the new generation of independent watchmakers who are transforming the scene. He apprenticed with French watchmaker Denis Coperchot, and then Jean-Baptiste Viot while studying at the Lycée Edgar Faure in Morteau. One of the winners of the Young Talent Competition sponsored by the FHH and F. P. Journe in 2018, Auffret made waves with his Tourbillon à Paris, which has since become a subscription series.

Breguet

Abraham-Louis Breguet spearheaded a number of inventions, including the over-coil hairspring and the tourbillon, which he first invented in 1795 and patented in 1801. It is no coincidence that he remains the most cited reference point for accomplished watchmakers centuries later, from George Daniels to François-Paul Journe.

Cartier

Founded in 1847 by Louis-François Cartier, the creativity and impact of Cartier over the course of its history is undeniable. King Edward VII once described it as “the jeweller of kings, and the king of jewellers.” Throughout the 20th century, Cartier’s global reach expanded, and the French jeweller has left its mark on the world of horology, perpetually creating elegant, refined timepieces, while remaining faithful to its core design principles.

Charles Frodsham

Charles Frodsham & Co is the oldest continuously trading firm of chronometer manufacturers in the world, dating back to 1834. Renowned for making marine chronometers, clocks, and pocket watches for the likes of J.P. Morgan and the British Navy. Today, the brand carries forward this heritage by restoring historic technical timepieces and, much more recently, creating their own wristwatches.

Christian Klings

Based in Dresden, Germany, Christian Klings has dedicated his career to the mastery of technical and artistic watchmaking. His work is focused on developing traditional mechanical escapement technology while keeping the spirit of traditional watchmaking alive, creating everything by hand. As a result, the watchmaker has only created a few dozen timepieces over the course of his career. Klings’s inventions include the intriguingly named “Mosquito” and “Desmodromic” escapements, while his watches are more typically special commissions for true collectors.

Credor

Originating in 1974, the Credor line is a subsidiary of Seiko, and possesses an entirely different persona from its more well-known parent brand. Made at Seiko’s Micro Artist Studio in Shiojiri, the workshop consulted with Philippe Dufour, one of the most talented independent watchmakers working today, to help establish the practices and techniques behind the creation of the pieces that now bear the Credor name.

Cyril Brivet-Naudot

French watchmaker Cyril Brivet-Naudot started working on the Eccentricity at the age of 29. He had just graduated from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland, but it could be said that the kind of watchmaking he would pursue was influenced by his time at the Lycée Edgar Faure in Mortau in his native France. Brivet-Naudot combines this respect for tradition – almost all elements are hand-made at his manufacture without the use of CNC – with a technical expertise, that has seen him reimagine the eccentric escapement.

Czapek

The Czapek and Cie brand dates back to 1845, launched by Franciszek Czapek. At the peak of their success, the brand catered to figures such as Napoleon, and had boutiques in locations such as the Place Vendome in Paris. After a period of dormancy, the brand was revived in 2015, and has since been known for their classically styled yet boldly designed watches.

Daniel Roth

Daniel Roth was born into a family with deep horological roots, and established his own manufacture in 1989. Despite his limited output, his work was incredibly varied, from double-ellipse cases to sharply executed pinstripe guilloché dials. Roth was one of the key brand names of independent watchmaking in the 1990s, alongside Franck Muller, Roger Dubuis and Francois-Paul Journe, among others.

David Candaux

The brand's journey officially began in 2017, but watchmaker David Candaux spent his early career working on complex pieces with the likes of Jaeger-LeCoultre, developing his skills as both an engineer and designer. The holder of multiple watchmaking patents, Candaux's penchant for innovation is clear throughout his watches, such as with his signature inclined tourbillon.

De Bethune

In 2002, David Zanetta and Denis Flageollet joined forces to establish De Bethune, united by their shared vision of what contemporary watchmaking could look like. Making a limited number of watches a year, the brand has combined time-honoured skills with cutting-edge technology, to carefully craft each piece entirely within the watchmaker’s atelier in the Swiss town of Sainte-Croix. Flageollet in charge of the technical and mechanical side of things, whilst Zanetta brings his input to the design and aesthetics.

Delaloye

When Nicolas Delaloye first charted an independent path in 2001, his first order of business was to devise a calibre of his own. While he procured the gear train from a vintage ébauche – the AS1130 – the rest of the calibre bore his unique vision. The process of development took three years. He paired it with a classical case, of the sort he had experience working with at Patek Philippe during his several stints with the brand.

Derek Pratt

One of the unsung heroes of British watchmaking, Derek Pratt dedicated his life to the pursuit of excellence in traditional watchmaking techniques. He began his career in restoration, before going on to work with Peter Baumberger to revive the Danish brand, Urban Jürgensen. The pinnacle of his career was his work on the Harrison H4, a passion project which was eventually completed by Frodsham & Co. after Pratt’s passing.

Ferdinand Berthoud

Ferdinand Berthoud was one of the most prominent names in the context of 18th century watchmaking and science. He was especially motivated to creating robust and reliable marine chronometres to aid global exploration. Berthoud’s Marine Clock no. 6 and no. 8 were sea-tested in 1768, and the results were so positive that he was awarded the royal charter of Clockmaker and Mechanic to the French King and his navy.

Florent Lecomte

Florent Lecomte began his career as a teacher at the Lycee Edgar Faure in Morteau in 2006, where he specialised in mechanical watches with complications. Some of Lecomte's pupils have included the likes of Remy Cools and Théo Auffret, all of whom have struck out on independent careers. Lecomte's own career as an independent began in 2020, during lockdown. As of today, he has produced three different watch series in limited numbers

F. P. Journe

As a talented young watchmaker, F. P. Journe restored clocks and pocket watches from Janvier and Breguet, completed commissions from Asprey and Cartier, all while working on his own projects. One day, his friend Camille Berthet suggested a subscription model. The Souscription Tourbillon was born, with twenty close clients and friends of the watchmaker committing a deposit that allowed the F.P. Journe manufacture to flourish.

Franck Muller

Franck Muller began his watchmaking career restoring watches for collectors and auction houses, including for the Patek Philippe Collection, gradually building a reputation for his skill in restoring complicated timepieces. In 1984, when tourbillons weren’t in favour, and were rarely found in wristwatches, Muller designed his first exposed, dial-side tourbillon watch. Muller finally launched his eponymous brand in 1991, with the headline “Master of Complications”. His work is a spectrum, characterised by the classically-styled pieces made in his earliest days, to the modern, tonneau-shaped cases and experimental dials.

George Daniels

Dr. George Daniels is recognised as one of the greatest watchmakers of the 20th century. In 1981, he received an MBE for his services to horology, along with a CBE in 2010 – the first watchmaker ever to receive such an honour. One of his most noteworthy contributions to watchmaking was the invention of the Co-Axial Escapement, designed to improve a mechanism’s long-term performance by radically changing the nature of its inner workings.

Gerald Genta

Gérald Genta is a designer that needs little introduction to those in the watch world. Perhaps most famous for designing the Royal Oak and Nautilus pieces for Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe respectively, Genta's designs also included the Universal Geneve Polerouter, the IWC Ingenieur, and the Seiko Locomotive. The last piece pays tribute to some of his most successful designs, and Genta had a very close relationship with the brand's president, Reijiro Hattori.

Girard Perregaux

A distinguished Swiss watchmaker, boasts a rich heritage dating back to 1791, making it one of the oldest and most revered names in the horology world. Renowned for its commitment to precision, craftsmanship, and innovation, Girard-Perregaux has consistently pushed the boundaries of watchmaking excellence.

Greubel Forsey

Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey met during their time at Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi in the early 1990s. They launched Greubel Forsey in 2004, introducing the Double Tourbillon 30° at Baselworld, and making their mark as specialists of complicated watches. Some of their notable watches include the Handmade 1, which won the Men’s Complication Watch prize at the GPHG awards in 2020, as well as the Grande Sonnerie, their most complicated watch to date, with 935 components.

Grönefeld

Bart and Tim Grönefeld grew up steeped in horology at their grandfather’s workshop, and later, cut their teeth at famed complications specialist Renaud et Papi, alongside notable contemporaries such as Stephen Forsey and Stepan Sarpaneva. Producing no more than 70 watches a year, the Grönefeld brothers create extremely high-quality pieces, having commanded the admiration and respect of M. Philippe Dufour, amongst others.

Haldimann

Only making several dozen watches a year, Haldimann Horology is a true independent manufacture. Honing the horological arts since 1642, Haldimann watches are crafted entirely within the watchmakers’ workshop in the Swiss town of Thun. One of the last remaining ateliers in the world capable of producing and restoring almost everything by hand, the essence of Beat Haldimann’s approach to his work, is the synthesis of art and technology.

H. Moser & Cie.

H. Moser & Cie has long-established roots within the words of horology, with the manufacture originally founded by in 1828 in St. Petersburg, Russia. During this period, Heinrich Moser’s clients included Russian princes, as well as members of the Russian Imperial Court. Many years later, in 2005, the brand H. Moser & Cie was relaunched, with Heinrich Moser's great-grandson involved in the project.Since then, H. Moser & Cie has created watches which combine classic styling, with a number of innovative features.

Jaeger-LeCoultre

During the 20th century, Jaeger LeCoultre was known for producing its own wristwatches, such as the Reverso and the Memovox, as well as creating an imaginative array of horological objects. With a wide range of different designs - from leather-bound travel clocks to miniature key pendants which tell the time - they were all powered by the manufacture’s own calibers. Their mechanical prowess was such that their movements also found themselves in the watches of Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet and Vacheron Constantin, among others.

Jean Daniel Nicolas

Since leaving his eponymous brand, Roth has continued to produce watches, under the name of Jean Daniel Nicolas - a combination of his son’s name, his own and that of his wife. All three of them work together in producing a small handful of pieces, with his wife also trained as a watchmaker and his son apprenticing under his father. Under this new venture, Roth has narrowed his focus, on what matters the most to him. He only produces about two to three pieces a year, all of them displaying an impressive level of craft and hand-finished details.

Jean-Baptiste Viot

French watchmaker Jean-Baptiste Viot began his career in restoration, first working at the International Museum of Watchmaking in La Chaux-de-Fonds, then briefly at Vacheron Constantin, before moving to Breguet in 1998, where he spent eight years. After that, Viot decided to strike out on his own, as an independent watchmaker. His first watches used the Peseux 260 movements, famously also used in Kari Voutilainen’s Observatoire pieces. Completely handmade, Viot’s watches draw inspiration from 18th and 19th century French horology.

Kikuchi Nakagawa

Kikuchi Nakagawa was founded by watchmaker Tomonari Nakagawa and designer Yusuke Kikuchi in 2012, when the pair met in Paris. At the time, Kikuchi was attending watchmaking school and would later go on to work in watch repair. Meanwhile, Nakagawa had originally trained to be a swordsmith, later applying those metal-work skills to watchmaking and finding employment with Citizen Watch Co. Their shared sensibilities and appreciation of watchmaking from the 1930s and metal finishing are evident in the brand's work.

Krayon

Krayon’s approach to watchmaking is deeply grounded in mathematics, with the brand being helmed by designer and engineer Rémi Maillat. Rendering complex concepts into metal, their watches the Everywhere and Anywhere are true mechanical feats, transforming the world of complications as we know it.

Laurent Ferrier

Prior to starting his eponymous brand, Laurent Ferrier worked at Patek Philippe for four decades, with his final position as creative director. Particularly reminiscent of classic Patek designs, we see a focus on maintaining tradition while creating watches that are contemporary and relevant. Laurent Ferrier is suited to the collector who appreciates excellent craftsmanship combined with modern aesthetics.

Lang & Heyne

Located in Dresden, Germany, the brand was created in the early 2000s by watchmakers Marco Lang and Mirko Heyne. In the earlier years, the manufacture grew to a team of just 10 watchmakers, producing 30 watches each year. Drawing inspiration from the Fürstenzug, a mural depicting the historical rulers of Saxony, their style adheres closely to classical aesthetics. while the watches range from elegant time-only pieces to impressively complicated examples.

Minerva

Minerva’s story begins in the year 1858, founded by brothers Charles and Hyppolite Robert, in the small town of Villeret, located in the canton of Bern, Switzerland. The company - initially called H & C. Robert Watch Co. - started off by using third-party movements, which they built into pocket watches. However, the brand soon came into its own and began to produce watch movements in 1895.

MB&F

MB&F’s philosophy is simple - the reinterpretation of traditional, high-quality craftsmanship into three-dimensional kinetic sculptures. The company’s relationship with many of haute-horology’s finest independent movement makers, coupled with careful choosing of its suppliers has led to the development of visionary modern timepieces, celebrated for their exceptional design and mechanical brilliance. A Collected Man is an official preowned approved partner for MB&F.

Oilean

Watchmaker John McGonigle founded his independent brand Oileán – pronounced ‘il-awn’ and meaning island in Irish – in 2020. The name Oileán reflects not just the watchmaker’s heritage but the fact that he works by himself. Although McGonigle initially began his career in Switzerland with his brother, Stephen McGonigle, his desire to explore his own watchmaking philosophy and aesthetic led John to become independent.

Parmigiani Fleurier

First introduced in 1996 by watchmaker Michel Parmigiani, The brand takes its name from its founder, Parmigiani, and the village in which it was founded – Fleurier, Switzerland. Parmigiani made a name for himself in the 1970s as a master restorer of vintage clocks and watches, and his workshop was where Kari Voutilainen first began his own watchmaking journey. Backed by the Sandoz Family Foundation, Parmigiani was able to begin creating original pieces, and the brand now boasts a rich 25 years of watchmaking.

Pascal Coyon

Based in the south-western French port city of Bayonne, Pascal Coyon worked as a watch and clock repairer before he embarked on an ambitious goal of creating his own chronometre wristwatch offered at an affordable price point. He was a student of the famed Lycée Edgar Faure in Morteau, which has produced many of France's best watchmakers.

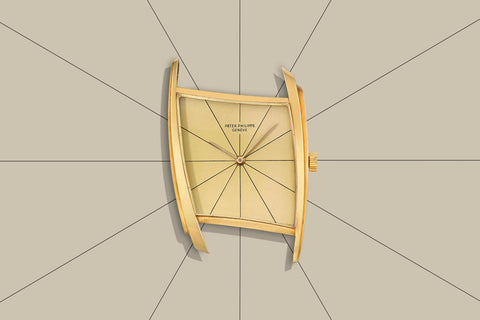

Patek Philippe

Patek Philippe, the blue chip of the industry, has long been seen as the premier manufacturer of haute horlogerie timepieces. A Patek Philippe reflects a certain discretion and quiet satisfaction in the wearer, preferring tastefulness and subtlety, with no pretense. Ranging from a simple, time-only Calatrava, to the ultra-complicated perpetual calendar chronograph, there is certainly a Patek Philippe for everyone.

Paul Gerber

One of the earliest AHCI members, Paul Gerber began crafting watches in his Zurich workshop in 1976. His work is a spectrum of traditional aesthetics and strikingly modern style, entirely made by hand. Alongside his own creations, Gerber has also worked on pieces such as the Louis Elysée Piguet Grande Complication, at one time the most complicated wristwatch in the world, in addition to helping Ludwig Oeschlin develop and prototype the MIH watch, an annual calendar with just nine parts.

Petermann Bédat

Gaël Petermann and Florian Bédat's story, from meeting at the Geneva watchmaking school to working closely with Dominique Renaud of Renaud Papi, then gradually building their brand’s vision, is one of partnership and collaboration. A Collected Man is honoured to be the exclusive European retailer for the independent watchmakers. If you would like to be notified about future projects, please register your interest. To find out more about Petermann Bédat, you can watch our film with the young watchmakers.

Philippe Dufour

Based in his atelier in la Vallée de Joux, Switzerland, Monsieur Dufour is a master of grand complications, basing his designs on the traditional movement architecture and artistic expressions of the Vallée de Joux from 1850 to 1920. With a long-stretching career and recent record-breaking auction result, Philippe Dufour is the undisputed king of finishing. Learn more about the Grande et Petite Sonnerie, the most expensive wristwatch ever sold publicly by an independent watchmaker here. A Collected Man is the approved re-seller of pre-owned Dufour Watches.

Raúl Pagès

Spanish watchmaker Raúl Pagès was born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and at the beginning of his career as a watchmaker, he worked in restoration with Parmigiani Fleurier and Patek Philippe, before moving on to start his own brand in 2010. His early experiments included automations, while his first watch was the Soberly Onyx, based on a vintage CYMA movement. The RP1 Régulateur à Détente was his first piece created entirely from scratch, and in 2024, he won the inaugural LVMH Independent Creatives prize for his work.

Ressence

A combination of the words renaissance and essentiel, Ressence is a young, independent brand with a unique approach to contemporary watchmaking. Their motto “Built on the expertise of yesterday, crafted with today’s technology, our watches are designed for tomorrow” - very much speaks to this, innovative identity. Founded by the Belgian industrial designer, M. Benoît Mintiens in 2010, all of the brand’s watches carry ever-changing regulator dials, in which the sub-dials and main-disc continually orbit one another.

Richard Mille

Founded by Monsieur Mille in 1999 in collaboration with the famed movement manufacture Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi, Richard Mille has demonstrated from the very beginning their taste for experimental, high-tech watches. When they released the RM001 tourbillon in 2001, it was just a hint of where the brand would progress over the subsequent decades, taking inspiration from the worlds of Formula One, aerospace and automotive research. With their motto of “a racing machine on the wrist" in mind, Richard Mille's designs reinforce the concept of performance, while innovation remaining at the core of the brand's identity, both in watchmaking and in materials-science.

Roger Dubuis

In the '80s, Roger Dubuis left Patek Philippe to establish his own workshop, dedicating himself to the restoration of older pieces. In 1995, following a partnership with businessman Carlos Dias, he would establish his own eponymous brand. Dubuis' attempt to rival Patek Philippe themselves became one of the reasons for his acclaim – his pieces channelled the traditional Geneva watchmaking that Patek Philippe embodied with more stylistic flair.

Roger W. Smith

Roger W. Smith OBE is recognised as one of the greatest watchmakers of the modern era. The only apprentice and collaborator of the late Dr. George Daniels, they worked on a number of projects together, from the Millennium series to tourbillon wristwatches. Roger W. Smith has since become the flag bearer for English watchmaking, building on the work of his mentor, but also on past luminaries like Tompion, Graham, and Arnold.

Romain Gauthier

Romain Gauthier’s entry into watchmaking was somewhat unconventional. Despite his upbringing in the Vallée de Joux, he initially chose to pursue his love for music and musical equipment as an area of study. Gauthier then pivoted, studying precision mechanics and then machine-tool construction. Whilst still at François Golay SA, Gauthier developed his first movement, which he worked on for over two years, using his employer's machines in evenings and weekends. He then went on to launch his eponymous brand, with guidance from other independent watchmakers such as Philippe Dufour.

Sarpaneva

As the son of jewellery designer Pentti Sarpaneva, and nephew of the internationally acclaimed designer and artist Timo Sarpaneva, it was always the case that Stepan’s career would take a creative direction. Educated at the Finnish School of Watchmaking and then WOSTEP, Sarpaneva was formed in Helsinki, Finland, in 2003. Inspired by his time at manufactures including Piaget, Parmigiani, Vianney Halter and Christophe Claret, Stepan demonstrates his passion for the craft in each watch to come out of the workshop.

Speake-Marin

Peter Speake is an English watchmaker whose career spans the UK and Switzerland. Starting out at Somlo Antiques, Speake became a specialist restorer of antique and vintage timepieces. Between 1996 and 2000 he worked for Renaud et Papi in Le Locle Switzerland, after which he developed the brand Speake-Marin with Daniela Marin. He remained active with the brand until 2017, then spent another 5 years in horological education. In July of 2022, Speake established PS Horology.

Sylvain Pinaud

Sylvain Pinaud is no stranger to the watch industry, having worked within it in various capacities before starting his independent brand. His experience is evident in his watches, demonstrating mastery of craft and a sharp focus on carefully chosen details. Pinaud’s style combines the industrial with the openworked, turning the tables on convention.

Thomas Prescher

Located in Ipsach, Switzerland, Thomas Prescher was a naval officer before he decided to become a watchmaker. He spent some time at Audemars Piguet, IWC, and Gübelin, and was the director of production at Blancpain. He founded his independent brand in 2002, and has become known for his work with tourbillons, as well as his unique commissions for clients.

Ulysse Nardin

Created in 1846, Ulysse Nardin has always been inspired by seafaring, creating chronometres of both the marine and pocket variety in these early days. After the Quartz Crisis, the brand was then revived in 1983 by Rolf Schnyder, former Jaeger-LeCoultre executive, and watchmaker Ludwig Oechslin, before becoming a subsidiary of the French group Kering in 2014. The association with seafaring has remained a constant, with the brand often serving as the official supplier to navies around the world.

Urban Jürgensen

Urban Jürgensen have a rich and varied history, dating back to the late 18th Century. The manufactures namesake, Urban Jürgensen (1776-1830), along with his father Jürgen Jürgensen have long been credited with introducing the watch industry to Denmark. Shortly after the birth of his son in 1776, Jürgen Jürgensen moved to Le Locle in Switzerland to work with Jacques-Frédéric Houriet, laying the foundations for a Danish-Swiss connection which still exists over 240 years later.

Urwerk

Urwerk is an award-winning watch brand based in Geneva, Switzerland, and is known for its avant-garde designs and new indications and complications. Founded in 1995 by watchmaker brothers Thomas and Felix Baumgartner (Thomas Baumgartner left in 2004) along with the artist and designer Martin Frei, they have quickly become a leader in innovative independent watchmaking.

Vacheron Constantin

Vacheron Constantin boast a lengthy and uninterrupted history of manufacture, dating back to 1755. The firm’s founder, Jean-Marc Vacheron, was one of many cabinotier-watchmakers who specialised in the production of complex components. Upon partnering with François Constantin, Vacheron (the brand) became widely known for upholding the finest horological traditions - enamelling, piercing, engraving and engine-turning.

Vianney Halter

From a young age, Vianney Halter was fascinated by mechanics, science fiction, and space exploration. He enrolled in the Ecole Horlogère de Paris, at the age of fourteen, and after graduating, spent the subsequent decade restoring vintage clocks and watches. Halter was then invited to join THA Èbauche, a collaborative movement manufacture, by F. P. Journe. In 1998, Halter unveiled his first watch, the Antiqua, whose futuristic aesthetics cemented the style which Halter has come to be associated with since.

Voutilainen

After a period spent restoring some of the finest watches from the last three centuries, Kari Voutilainen became an independent watchmaker. His work has been welcomed with great acclaim, on account of its unique aesthetic and quality. Every component in his watches involves manual labour, from adjusting tolerances to polishing and angling. His efforts have been recognised with more than a half dozen awards from the GPHG (Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève).

Winnerl

Helmed by Bernhard Zwinz, a watchmaker highly regarded amongst fellow independent makers, his work is produced under the name of his Austrian compatriot, 19th century watchmaker J.TH. Winnerl. We are great admirers of Zwinz’s craft and his dedication to perfection. Creating his watches entirely by hand, his experience and talent holds the promise of many exciting projects to come.

In Focus: Haldimann H1 Flying Tourbillon

May 2025

• 2 min read

An introduction to Rexhep Rexhepi

April 2025

• 8 min read

The Philosophies of Stephen Forsey

April 2025

• 10 min read

What Makes Gratté Finishing So Special?

March 2025

• 2 min read

An Afternoon With Rémi Maillat

March 2025

• 7 min read

An Afternoon with Luca Soprana

November 2024

• 8 min read

A Collectors' Guide to Urwerk : Part One

October 2024

• 30 min read

A Collectors' Guide to Urwerk : Part Two

October 2024

• 20 min read

Looking Back to Look Forward at the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet

October 2024

• 20 Min read

The Morteau Makers: What drives Théo Auffret?

August 2024

• 10 min read

The Story of Atelier de Chronométrie

June 2024

• 16 min read

A Collectors' Guide to Urwerk : Part One

October 2024

• 30 min read

A Collectors' Guide to Urwerk : Part Two

October 2024

• 20 min read

A Collector’s Guide: Early F.P. Journe, Chapter One

May 2020

• 22 min read

A Collector's Guide: Patek Philippe 3800 Nautilus

August 2020

• 30 min read

A Collector’s Guide: Parmigiani Fleurier

December 2022

• 20 min read

A Collector's Guide: Asymmetrical Watches

February 2023

• 34 min read

A Collector's Guide: The Datograph

December 2021

• 21 min read

A Collectors Guide: The Patek Philippe 3940

April 2020

• 22min read

Collectors Guide - Early Daniel Roth

February 2021

• 20min read

An introduction to Rexhep Rexhepi

April 2025

• 8 min read

The Philosophies of Stephen Forsey

April 2025

• 10 min read

What Is Independent Watchmaking?

December 2021

• 19 min read

Discovering Bernhard Zwinz

March 2023

• 10 min read

An Afternoon with Raúl Pagès

June 2022

• 9 min read

A Brief History of De Bethune

June 2022

• 19 min read

In Focus: Haldimann H1 Flying Tourbillon

May 2025

• 2 min read

What Makes Gratté Finishing So Special?

March 2025

• 2 min read

The Art of Dial Finishing

September 2021

• 15 min read

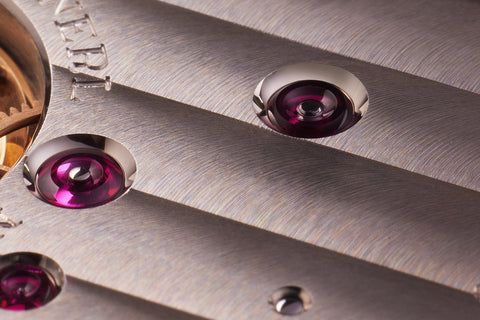

The Art of Movement Finishing

February 2024

• 13 mins read

Has Minimalism In Watch Design Gone Too Far?

May 2022

• 18 min read

The Bare Bones Of the Skeletonised Watch

December 2021

• 8 min read

Rediscovering the Romance of Travel Clocks

September 2023

• 7 min read

What Made the Royal Oak a Cultural Icon?

June 2023

• 22 min read

Can We Compare Art and Watches?

October 2021

• 9 min read

Why Does Provenance In Watches Matter?

July 2022

• 18 min read

How Five Collectors Under-30 Approach Watches

August 2021

• 14 min read

A Potted History of Japanese Whisky Collecting

December 2021

• 10 min read

The Philosophies of Ross Lovegrove

February 2022

• 9 min read

Interview: Torafu Architects

July 2022

• 7 min read

An Afternoon With Rémi Maillat

March 2025

• 7 min read

An Afternoon with Luca Soprana

November 2024

• 8 min read

The philosophies of Stephen McDonnell

January 2024

• 20 min read

A Closer Look at Collecting with Doo Sik Lew

June 2022

• 9 min read

George Daniels the Collector

July 2021

• 8 min read

Interview: Jason Jules

February 2022

• 7 min read