Four Patents that Changed the Face of Watchmaking

It could be said that patents have lost their impact in watchmaking. Nowadays, they’re often tallied up on press releases, in order to sway consumers or impress journalistic outlets. Historically though, patents and the innovations they’ve covered have played a key role in pushing watchmaking forwards.

Not only do they protect inventions, but they also help to document them. This effort means that we’re able to look back at the technical drawings of Abraham-Louis Breguet or examine the earliest incarnation of the Oyster case. A paper trail such as this can shed light on how the watch world has progressed, from pendulum clocks to the swinging rotors of automatic wristwatches.

The mythical world time patent.

This is why we wanted to take a look at four specific patents, what led to their filing and what difference they made to horology. From one of the most famous patents filed in watchmaking, the tourbillon, through to the Oyster case, the world time mechanism and the self-winding movement, all of these have impacted watchmaking today.

The Oyster Case

Water resistance is now so ubiquitous that it has almost become an afterthought when listing the features of a certain model. It’s assumed that almost any modern watch will be able to withstand a certain amount of water pressure, no matter its intended function or integrated complication. This is how commonplace this feature has become. While Hans Wilsdorf and his team at Rolex are credited with inventing the first “waterproof” case – although the term water resistant is favoured today – that doesn’t quite capture the whole story. Released by Rolex in 1926, the Oyster case was the first commercially successful execution of the idea, building on previous patents and advances in sealing off wristwatch movements.

The issue of water resistance was only ever approached seriously once wristwatches appeared, in the early 20th century. Prior to this, pocket watches were never particularly exposed to the elements, as they were stored in a pocket, or in a wooden box, in the case of marine chronometers. It was the soldiers of World War One who first started to wear watches on the wrist, proving the usefulness of this approach, whilst also challenging the widely held notion that wristwatches were effeminate.

There were various water-resistant pocket watches made prior to this, such as the Alcide Droz & Fils Imperméable model, which began production around 1883. This was made possible by the developments of Dennison and Ezra Fitch. It was the latter who secured two patents in the late 19th century, one for a swing ring case with a screw cap and another for a screw-down crown.

Rolex's design, courtesy of Jakes Rolex World and Perezscope.

There was also a later patent filed by François Borgel, in 1891, for a water resistant screwed in pocket watch case. These advancements gradually appeared on the wrist. One of the first instances of this came in the form of the Submarine Commanders watch, which was released in 1915. It featured both a screw-on caseback and screw-on bezel, both of which helped keep moisture out of the watch. The design was so noteworthy that it was covered by an entire article in the Horological Journal in 1917.

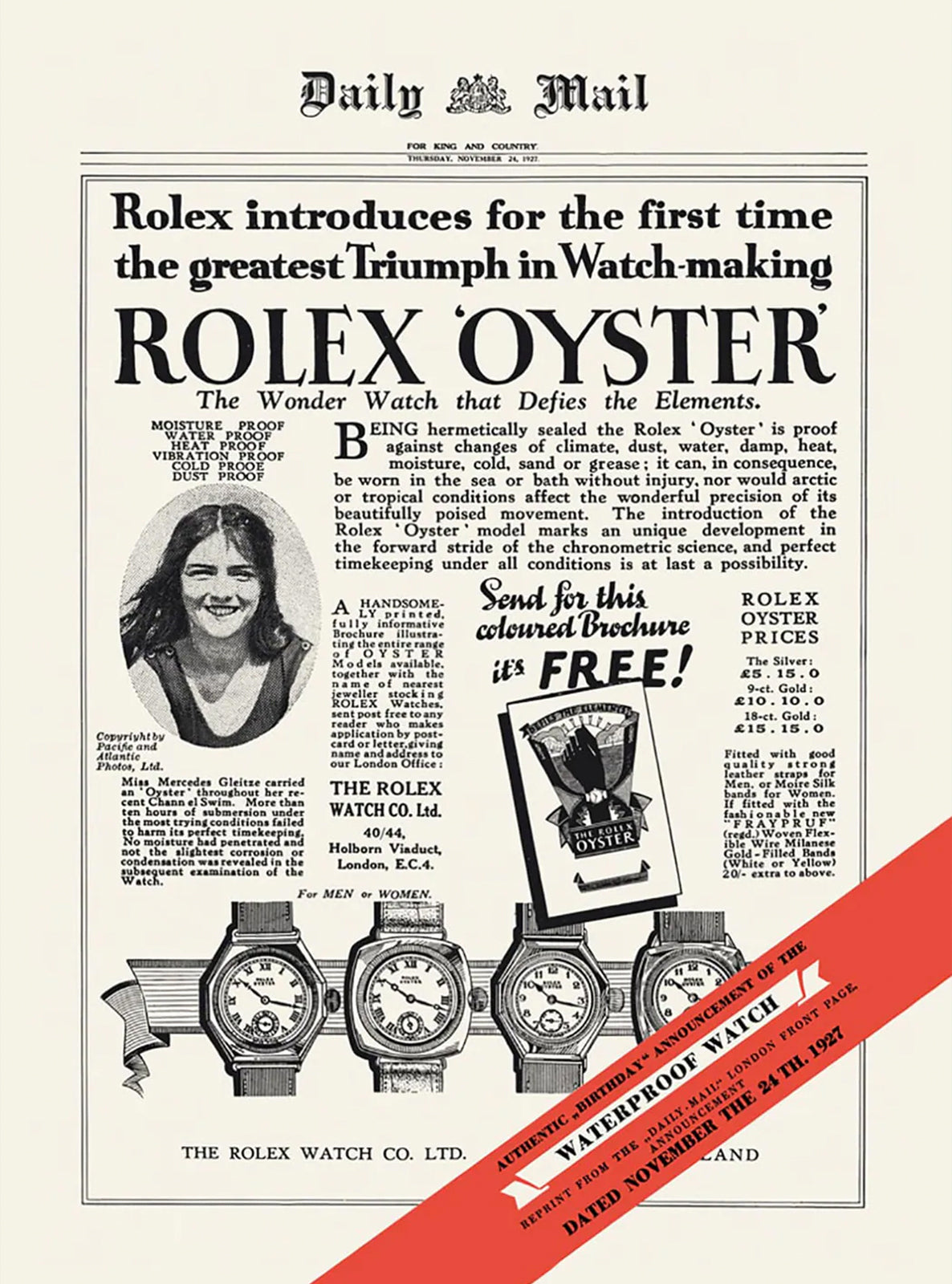

So, why is Rolex credited with inventing the waterproof watch, if many of these patents pre-date the company, which was first founded in 1905 under the name Wilsdorf ad Davis? There are two reasons. The main one is that Wilsdorf made the idea commercially successful, for the very first time. He gave a Rolex Oyster to Mercedes Gleitze, when she attemted to swim the English Channel. The watch - tied around her neck and not on her wrist - withstood the lengthy swim and was used to launch an advertising campaign for the Oyster. To this day, Rolex still uses Gleitze's name in their publicity.

An original Rolex Oyster, first released in 1926, courtesy of Rolex.

The other progression which can be attributed to Wilsdorf is the invention of a tool that enabled the back and bezel of the watch to be screwed on tighter. For this, he was granted patent number CH 143449, which was published on 15th November 1930. This not only marked the birth of the Oyster watch, but also of Rolex’s recognisable fluted bezel, which was used by this innovative tool to grip onto seal the front of the watch.

Wilsdorf’s marketing of the design didn’t stop with Rolex. He also created a sister brand named Oyster, very similar to what he would later do with Tudor. These watches used the same sealing technology as the Rolex models but were made from cheaper materials and were fitted with lower grade FHF calibres, rather than the Aegler ones used by Rolex. A number of these were supplied to retailers such as Abercrombie & Fitch.

A select few Oyster pocket watches were also made, with a characteristic cushion-shaped case. As you might expect, they never really took off, as there was little call for water resistant pocket watches. However, these would later become the foundation of the very first Panerai watches, launching an entire brand from a once unsuccessful product.

Rolex have always proudly advertised their product’s resistance to water, courtesy of Watchmen Times and Rolex.

This is a great example of how the watch world, as a whole, was working towards a certain goal at a very similar time, and it just took one extra push to get it over the line. It was an amalgamation of these patents that led to the Oyster case, with brands later competing to see who could take their watches to greater depths.

The Tourbillon

This is possibly the most famous patent in all of horology. Unlike the Oyster case, the tourbillon was the result of one man working in isolation from everyone else, in order to find a solution to a long unsolved problem. While the patent for the tourbillon was awarded to Abraham-Louis Breguet on 26th June 1801, he actually invented the complication six years prior, in 1795.

The technical drawing produced by Abraham-Louis Breguet for the patent of his tourbillon, which was published in 1801, courtesy of of l'Institut National de la Propriété Indistruelle in Paris.

The complexity of this whirling escapement was clear from the fact that it took Breguet four years to produce a watch containing a tourbillon which he could sell. It then took another nine decades for a similar device to be conceived, when the Danish watchmaker Bahne Bonniksen invented the Karrusel in 1892. As it was easier to construct than the tourbillon, the Karrusel opened up greater accuracy to a larger number of watchmakers and clients, though it lacked the technical finesse of Breguet’s invention.

Two vintage pocket watches, one containing a tourbillon and the other a Karrusel.

Able to compensate for the effects of gravity on the balance spring, the tourbillon solved one of the biggest issues facing pocket watches at the time, as they spent the majority of their life sat upright in a pocket or on a stand. The constant pull of gravity in one direction usually warped the thin balance spring, affecting its rate and how accurately the watch kept time.

It was conceived when Breguet had just returned to Paris, after he’d been in self-imposed exile in Switzerland in order to escape the Reign of Terror wreaking havoc in the French capital. Clearly a turbulent time in the watchmaker’s life, it makes the fact that he was able to conceive such a device all the more impressive.

Contemporary tourbillons from George Daniels and François-Paul Journe.

Today, the tourbillon has taken on many forms, and has been advanced far beyond anything Breguet could have envisioned. Flying, double, angled and gyro are all prefixes now attached to the French word for whirlwind. Even if some will say the complication is defunct in a wristwatch, we’re glad that it’s still around today, with classic examples being produced by watchmakers like Daniel Roth or François-Paul Journe, both of which list Breguet as one of their sources of inspiration.

The Self-Winding Watch

Many will be familiar with the story shared by Rolex about the introduction of the “perpetual” watch, their first automatic timepiece powered by the movement of the wrist. However, the history of self-winding watches dates back as far as the 18thcentury. This is one of the many instances where multiple watchmakers were working towards the same goal, at a similar time, and so pinning down the achievement to a single craftsman can be tricky.

An early self-winding movement with a side-weight made by Recordon, Spencer & Perkins, courtesy of Sotheby’s.

There are, however, a few defining moments that we can point to as real milestones in the development of what we now know as the modern, automatic movement. The first major swing in this direction came from the Swiss watchmaker Abraham-Louis Perrelet. In 1777, he invented a watch with a rotor that would swing up and down, which reportedly required 15 minutes of walking to fully charge. This would come to be known as a side-weight. That same year, Abraham-Louis Breguet also started to look into the problem, but made no real strides at the time, as any solution would have proven much too costly to produce for his clients. It took Breguet coming across Perrelet’s work for him to reengage with the idea in 1779, which he then kept refining until about 1810.

During this period, there were four different types of automatic movements being produced for pocket watches. There was the aforementioned side-weight, illustrated in a patent from the English watchmaker Louis Recordon, number 1248. Then you had the centre-weight, which differs from what we know today, as the weight is blocked by a bridge and so can only rotate roughly 180°. Next, the rotor-weight, a rare approach at the time, is very similar to what you would see in a modern automatic watch. Finally, the movement-weight involves the entire movement pivoting inside the case. This was an extremely rare construction, as only one was ever made, in 1806.

The technical drawing that was attached to John Harwood’s “bumper” automatic movement patent.

It’s not until the 1920s that we see automatic movements appear in wristwatches. Léon Leroy developed a side-weight system in 1922, and then just a year later, John Harwood, a watch repairer from Bolton, England produced a centre-weight or bumper movement. This rotor swung 180° and would only wind the main spring in one direction. Having the weight bounce off its spring bumpers theoretically produced more back and forth motion, which helped wind the mainspring more efficiently.

This approach allowed the watch to be sealed off, by removing the crown and transferring the setting of the hands to a rotating bezel. These pieces were made by a number of different manufacturers around the world, including Blancpain in France. It’s estimated that about 30,000 of them were produced worldwide before 1931, when Harwood’s company collapsed under financial pressure from the Great Depression. Of course, many will be familiar with what came next, as Rolex improved on Harwood’s work with the Perpetual movement. With a rotor spinning a full 360° and a mainspring which could store a greater amount of energy, the movement could run for 35 hours once fully charged.

An early Harwood self-winding watch without a crown and an early Rolex Oyster Perpetual, courtesy of Sotheby’s and Rolex.

Since Rolex began to take centre stage at the same time as Harwood’s company began to struggle, they were often criticised for overlooking the advancements made by the Brit. It wasn’t until 1956 that Rolex officially credited Harwood for inventing the self-winding wristwatch, even including portraits of him in their advertising material, alongside an image of Perrelet.

The World Time

The world time complication represents another instance where various watchmakers were attempting to solve the same issue over a period of time. Eventually, all it took was one person to perfect a system that had been in development for a number of decades. Louis Cottier managed to piece together the advances made before him at the opportune moment, launching what would become one of the most recognisable dial layouts in history.

The recognisable face of Patek Phillippe's World Time watches, made possible by Louis Cottier, courtesy of Phillips.

There had been numerous attempts to produce world time pocket watches from the 19th century onwards, with varying degrees of success. They never caught on, as there was no real need for them. Most towns during this period had their own local time, based roughly off their solar time, meaning that midday would be a slightly different in London and Cardiff. As travel and communication between two locations such as these was often particularly slow, this didn’t have much effect. However, as we studied in our article on the relationship between travel and time, it was the advent of the railways that would trigger a standardisation of time.

Technical drawings of Cottier’s from two patents he filed for his world time and its various progressions.

Not only was the world shrinking due to rail travel, but the use of telephones was becoming more widespread. This meant that watch brands were trying to find ways of calculating the differences between time zones, in order to facilitate communication. While the Prime Meridian Conference in Washington D.C. unified the 24 time zones in 1884, it wasn’t until 1931 that Louis Cottier would debut his first world time watch.

An order placed by Rolex in 1948 for dials for their world time pocket watches from Stern Frères Fabrique de cadrans, courtesy of Rolex Magazine.

Cottier’s design allowed for the time in all 24 time zones to be displayed at once, using a single set of hands and a rotating inner bezel. First licensed by Vacheron Constantin in 1932, it was Cottier’s work with Patek Philippe that would prove to be the most significant. The first model that they produced together was the rectangular ref. 515 HU, in 1937. Cottier would go on to help develop his movement with Patek Philippe for the next 30 years, until his death in 1966. He also supplied movements for Rolex and Agassiz – now Longines – who put his work inside the pocket watches gifted to the allied leaders at the end of World War Two.

The dial and movement sides of a Patek Philippe World Time that still includes city names such as Bombay and Saigon, courtesy of Christie’s.

During his time working with Patek Philippe, Cottier improved on his movement a few times. One of the big leaps forward that he made was enabling the city disk to be rotated via a second crown. This system was patented by Patek Philippe in 1958. This meant that the hour hand could now be moved without affecting the progression of the minute hand. After Cottier’s death, his workshop was gifted to Geneva’s Musée d’Horlogerie et d’Emaillerie where it can be visited today. A touching tribute to a watchmaker who brought us world time and so much more.