What is Independent Watchmaking?

By A Collected Man

Giving a straightforward definition of independent watchmaking is a near impossible task. In recent years, the question has become even harder to answer – ask any collector what they would define as “independent” and you’ll almost certainly get a wide range of answers, each drawing different parameters for the category, or defining it by completely different rules.

Notably, a condition for becoming a member of the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI) is that the watchmaker should “independently develop and produce their creations” but, once again, leaves the word “independent” up for debate. In the context of the AHCI’s creation, we can perhaps comfortably assume that they mean watchmakers who are independent of big brands or larger conglomerates. But since then, the world of independents has only grown and, with it, the many different interpretations of watchmaking that each artisan brings to the table.

At its very core, the term “independent” is defined as “not [being] influenced or controlled in any way by other people, events, or things”. Within watchmaking, this does not only have financial implications, but can also have creative, technological, or literal ones, especially regarding the watchmakers themselves. We break down a few of these binaries in an attempt to make sense of the factors that feed the debate.

Size and Financial Means vs. “The Struggling Artist”

A Patek Philippe Calatrava next to a Daniel Roth Tourbillon – the former made by a much larger manufacture, while the latter was crafted by an independent maker.

The first impression that comes to mind when we think of an “independent watchmaker” might be an overly romanticised one. As collector Steve Hallock, founder of TickTocking, and former president of MB&F North America, puts it, “If you asked most people to describe what they imagine when they think of Rolex, they think of a very quaint Swiss chateau with one watchmaker who’s toiling over this one watch for a very long time. Then, of course, you get into it and you realise that’s totally not what Rolex is. People get disillusioned with Rolex once they realise how big it actually is – but these smaller independents are the closest thing to that romantic ideal in the watch world, very much the Platonic ideal of a watchmaker.”

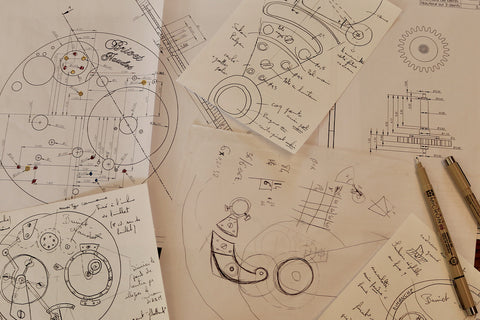

George Daniels is perhaps one such example. A famous British independent watchmaker who needs no introduction, he stands out as a pillar of this community, a man utterly dedicated to his craft, working in almost complete solitude on a tiny island away from the rest of the world. From the fight to be acknowledged for his work on the Co-Axial escapement, to the books that he wrote to help revive traditional watchmaking and to instruct individuals in how to make a watch completely from scratch, Daniels undoubtedly fits into the Platonic ideal of what it means to be an independent watchmaker.

The clean lines of a classic Calatrava, a flagship model of Patek Philippe since its introduction in the 1930s.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have the rise of Franck Muller. As a young craftsman, Muller was an independent watchmaker who wasn’t the most “traditional” of artisans. He wasn’t afraid to take risks and to bring his own style and flair to the craft, allowing his creations to grow in the spotlight. While Muller’s path was certainly focused on innovation and the extremes of complication making, Franck Muller the brand has changed drastically since the early days of its inception. Now producing close to 40,000 watches per year, and with Muller no longer part of the creative decision making, collectors might be hard-pressed to call the modern incarnation of his eponymous creation, a truly independent brand.

Other watchmakers have managed to find a balance between the two poles, such as F.P. Journe or Daniel Roth. Both have used traditional methods of watchmaking, but with their own distinct styles and designs. However, while both started out as small independents, they have since grown and have had dealings with bigger brands in very different ways.

An early Daniel Roth tourbillon, one that bears his name – later versions after the brand was acquired bear the Bulgari name instead.

Does investment from a larger company or several investors undermine a watchmaker’s “independence'? Sometimes, we do see a noticeable change of identity and style. When Bulgari acquired the Daniel Roth brand, his name became progressively subsumed under their's, with many of the tourbillons now bearing Bulgari’s mark. Just one year after the purchase, Roth left the brand he had started and began a new life as an independent watchmaker once again, under the name Jean Daniel Nicolas. Clearly showing that this new ownership was not the independent life Roth was hoping for. Now producing watches at a rate of two a year alongside his wife and son, Roth has returned to his independent roots, creating watches that he is truly passionate about, without the direction of a third party.

Conversely, we have seen success stories when independent watchmakers bring in investors, such as in the case of the luxury fashion powerhouse Chanel, acquiring a stake in F.P. Journe back in 2018. Although it may not have been a majority share, having external backers and the financial security that comes with this, is markedly different from a watchmaker that lives watch to watch. Despite that, Journe still retains much, if not all of his creative autonomy as the head of the brand, and with the safety of his backers, has, to some extent, a greater freedom to produce creative pieces. Take the recent Only Watch Journe and Francis Ford Coppola collaboration – markedly different from any of Journe’s past creations, yet highly innovative, it showcases a type of playfulness that perhaps could not be afforded in the very earliest days of the brand when Journe was still trying to establish himself as a serious craftsman.

One of the first 20 “Souscription Tourbillons” (left) made by Journe at the start of his career, beside a more recent collaboration with Francis Ford Coppola made for the 2021 Only Watch auction (right), courtesy of Hodinkee.

Another factor that comes into play is the support of auction houses and who they decide to curate and sell. The reach and influence of these houses is indisputable, but their interest in independent watchmaking is still recent. Sotheby’s held an auction of George Daniels’ watches in 2012 and have steadily increased the number of his pieces that they list. Meanwhile, in the Phillips catalogue from May 2021, they highlighted that they launched a section dedicated to Independent Watchmaking in 2018, just three years ago. Although they have produced excellent results and astounding sales for independent watches – a testament to the growing interest and excitement surrounding the pieces – when we take a cursory glance at their catalogues, we see that mainly older and more established watchmakers from the past 20 years still dominate. This proves that, while many of these pieces are simply easier to come by, to these auction houses, brand presence and recognition is still crucial – a point which we will explore further in the next section.

George Daniels and Roger Smith – two generations of independent watchmakers whose pieces regularly set new records at auction houses, courtesy of Roger Smith.

In his preface to the book Masters Of Contemporary Watchmaking, Michael Clerizo argues that “partly, independence is about the mundane wish to be your own boss. More importantly, it is about wanting to use your skills solely in the service of your own creative urges rather than the demands of a corporation or the whims of consumers. Independence is also about a belief that someone exists somewhere who will appreciate you and what you have done.”

Clerizo’s statement on the definition of independence leaves us with the distinct feeling that, above all, these watchmakers are people, not machines. Struggling artists or not, each takes control of their independence because they have a personality that will not be restrained, and this is freely expressed within their creations.

Brand vs. Person

An Audemars Piguet Star Wheel (left) next to a Rexhep Rexhepi Chronomètre Contemporain (right).

What makes a brand?

To play devil’s advocate: if we consider the definition of independent watchmaking to strictly include brands that are not part of a portfolio within a bigger group, then names such as Patek Philippe or even Audemars Piguet, not technically owned by conglomerates, are also independent watchmakers.

While these brands certainly don’t advertise themselves as such, they leverage their brand heritage and beginnings, with Patek Philippe even proclaiming that it is “the last family-owned Genevan luxury watch manufacturer”, recalling its humbler origins. Yet it also uses the term “manufacturer”, rather than watchmaker – a knotty piece of terminology that we will untangle later on in the next section. If your first instinct was to scoff at this reasoning, it’s not a surprising reaction – after all, brands such as Rolex or Richard Mille have reached a level of fame that has allowed them to gain widespread public acknowledgement of their craft, in contrast to the many independent watchmakers who remain relatively unknown.

Founded by Jules Louis Audemars and Edward Auguste Piguet in 1875, can the modern-day Audemars Piguet truly still be considered independent?

Famously, independent watchmakers such as Roger Dubuis, Philippe Dufour, and Kari Voutilainen started out working for bigger brands like Patek or Breguet, eventually getting tired of watching their work and innovations be released under a different name, and not being able to mention their involvement at all. These experiences would then catalyse their transition into working under their own identity. In turn, they have become brands themselves, both in terms of the cult following that their work has found but also the endless mythologising of their journey to becoming independent.

“If you asked most people to describe what they imagine when they think of Rolex, they think of a very quaint Swiss chateau with one watchmaker who’s toiling over this one watch for a very long time. Then, of course, you get into it and you realise that’s totally not what Rolex is.”

Further to this, there exists a nostalgia for the early work of brands-slash-watchmakers that were once independent, but have since been absorbed into bigger labels, or transformed into larger brands entirely such as Franck Muller, Roger Dubuis, or Daniel Roth. It speaks to a wider longing for perhaps a “purer” type of watchmaking, reminiscent of the idealised vision of what a watchmaker is.

Brands, Boutiques, Collectors

However, the bigger or more recognisable your brand becomes, the less straightforward it is to manage your brand and retain your identity as an independent watchmaker. When asked about how he balances the two roles, Felix Baumgartner, master watchmaker and co-founder of the intriguing brand, Urwerk, pointed out that “both [those roles] are complete opposites and, especially when you start running your own boutiques, you start running into problems, as you seem to be running more of a commercial company rather than a creative company. At Urwerk, we try to limit the watches that we make each year, and not go too much into the commercial side of the business. We present and explain our watches, but we don’t sell our watches.”

Felix Baumgartner and Martin Frei, co-founders of Urwerk, image courtesy of Urwerk.

Jacopo Corvo, current CEO of the GMT Italia SRL boutiques, one of the first retailers to promote and champion independent watchmaking, also has a similar outlook, having dealt with many different sizes and shapes of independent watchmakers of the years. He brings up the fact that while many brands are certainly capable, “some of them have faced problems in the past due to mismanagement, especially when they were too small, and the creators were doing too much themselves. Sometimes [the watchmakers] were doing everything, from the creation process to selling the watches at fairs, and the marketing, like answering emails.”

But smaller independent brands inevitably allow for a more personal connection between the watchmaker and collector, in addition to the retailers themselves. “Our relationship with these independent watchmakers is built entirely on trust,” says Corvo. “We work with people rather than brands.”

On the other hand, however, Corvo speaks about the difficulty of trying to work with independent brands that have expanded incredibly rapidly. “We were official retailers with Richard Mille years ago, and it slowly became impossible to work with them as their structure and production grew so quickly,” he says. “In the end, they chose to open their own boutiques. Yet you also have other independents which completely disappeared. Regardless, we make sure [we are] always in touch with the creator of the watches, even if there is a sales manager in between.”

The connection between a watchmaker and a collector can be very personal, with relationships stretching back to the very origins of these independent makers.

Highlighting this personal connection, Corvo adds: “Until just a few years ago at Baselworld you could walk around the independents section and talk to people like Kari Voutilainen, Felix Baumgartner, or Max Büsser. It was easy – they were just there. It makes the collector feel special. There is also the fact that people like Edouard Meylan from H. Moser & Cie or Max Büsser take the time to answer nearly every single DM and comment on Instagram. That’s crazy! Imagine how busy they must be and how much time it must take them in a day to reply to everything. With a bigger brand, this would be impossible.

“But of course, we [also] have the other extreme, where the watchmakers are so focused on their craft that they don’t even reply to our emails. But everyone has their own way of working.”

“Until just a few years ago at Baselworld you could walk around the independents section and talk to people like Kari Voutilainen, Felix Baumgartner, or Max Büsser. It was easy – they were just there. It makes the collector feel special.”

David, a longstanding private collector in the community, also brings up his time at Basel as being instrumental in getting to know these watchmakers. “To me, the purchase of the watch was more about getting to know the watchmaker, visiting them, seeing how they did it,” he says. “So, every watch that I bought became an association, a friendship, or a moment.”

Ultimately, can we separate the watchmaker from the brand? For an independent, it can sometimes be difficult to manage both sides of the playing field, but there is no question that it gives the collector a more personal relationship with the creator of their watch, in addition to opening a line of conversation that allows for the watch to be tailored to the wearer.

Handmade vs. Machine

A Habring² Doppel 2.0 (left) beside a Roger Smith Series 1 (right). Both come from independent makers, but who use different methods to make their watches.

How much of a watch does a maker have to make by hand before it can be considered an independently made watch? After all, isn’t there also a case to be made for watchmakers adapting and changing with the times, using technology to their advantage for their new creations?

The formation of the AHCI is crucial to our discussion of the skills required of a watchmaker, whether it’s creating by hand or with the help of machines. Formed in 1985, in the aftermath of the Quartz Crisis, they were the biggest proponents of the independent watchmaking community.

When we spoke to Svend Andersen, originator of the brand Andersen Geneve and co-founder of the AHCI, for his view on how the Académie helped shape independent watchmaking, he was charmingly dressed in a white watchmaker’s apron, with a loupe attached to his glasses – showing that at 79 he is still getting hands on. “The rules of the AHCI today are the same as when we first started it,” he says. “They have to be independent, and they have to be able to make a watch and present it at an exhibition, but, crucially, they have to be able to execute it themselves. The watch has to be a finished product to a certain level of quality.”

Andersen at the beginning of his career, with the infamous “Bottle Clock”, alongside a Worldtime watch, created after the foundation of his eponymous brand, courtesy of Andersen Genève.

In fact, the AHCI was once so small that Andersen says “there were a few independent watchmakers around Geneva, but there weren’t enough. We had to send out a press release to all the watch magazines in the world – at that time there were only 12! And out of those 12, seven of them published it, and we took in some members from Germany and France. One morning, I got a letter from England. I opened it, and it just said, ‘I want to join your group, signed, George Daniels.’ So, after that, we said yes, we are on the right path.”

This focus on skill is something that also distinguishes an independent watchmaker. Andersen places a particular emphasis on the fact that these watches must be complete and must work – a practical and, at most levels, fundamental definition of a watchmaker. But Andersen notes that the craftsman does not necessarily have to make the entire contents of the watch themselves, specifically referring to the movement.

“Independence is also about a belief that someone exists somewhere who will appreciate you and what you have done.”

However, in keeping with shifting definitions, and the fact that the world of watchmaking has expanded to include architects, engineers, and artists, Hallock disputes that independent watchmaking should only consist of watchmakers. “You definitely need to have a specific talent and a strong point of view,” he says. “They don’t have to be a watchmaker. Neither Max Büsser nor Romain Gauthier [are] a watchmaker, but they have real skill.”

If we consider production numbers within the watch world, we see brands such as Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet increasingly using CNC machining in order to produce more watches. This is where the term “manufacture” comes into play, which implies a more factory-scale approach. However, machines are not only used for large-scale production.

Meanwhile, we more often associate low production numbers with the idea of a maker taking a painstakingly deliberate approach to creating a watch, a masterpiece almost entirely fashioned from hand. As mentioned earlier, Baumgartner comments on the fact that they limit the numbers of watches they make, producing only about 150 to 200 each year, allowing them to avoid feeling like a production line, and dedicating care and attention to each piece.

David recalls observing Philippe Dufour trying to combine the two worlds. “He taught himself how to use a computer to design his watches, digitise, and use CNC, while at the same time, you would see him there – this classic watchmaker in this little schoolhouse, sitting there [doing everything by hand] and making sure all the angles were perfect,” he says.

These machines can almost certainly produce parts with more accuracy compared to traditional lathes, and have afforded makers the space to conceptualise and model potential creations. Some watches would never have come into being if it were not for CNC machines – take for example, the inventive Urwerk watches. As Baumgartner notes, “We keep it very open, and use a combination of hand-finishing and machine-made parts. We don’t have a problem with using machines but, most importantly, we keep an open mind to using whatever materials and methods that are necessary to help us achieve our vision.”

On closer inspection, the difference in a machine finished movement, and one done completely by hand begins to shine through.

When we look at the movement of the Habring² chronograph, we see that a degree of CNC machining is involved to create parts that can be more precise and accurate compared to those made by hand. This can make it look visually more uniform, with the difference between hand and machine finished calibres becoming one factor that differentiates various independent makers. With watches made by Roger Smith, the final piece is then hand-finished to an exceptionally high degree and assembled, all according to the Daniels Method, making the role of machinery ultimately a small one.

A common debate that has arisen within the community, however, is that watchmaking schools are not teaching their students to make watches, instead just teaching them to do two or three specific things. This results in these students not truly understanding the entire process. They then fill the ranks of retailers or manufacturers, which, thanks to the increased mechanisation of the industry, creates a vacuum of watchmaking knowledge where skills are not being passed down in the way that they might. This becomes particularly apparent in after-sales care, as many bigger brands focus less on trying to fix a problem, but rather simply on replacing parts until the watch begins to work again. This is harder to do with watches made by independents, given that some parts are not mass-produced or were built upon from older watches, for which the parts are no longer produced.

“The rules of the AHCI today are the same as when we first started it, they [the watchmaker] have to be independent, and they have to be able to make a watch and present it at an exhibition, but, crucially, they have to be able to execute it themselves. The watch has to be a finished product to a certain level of quality.”

As a factor in independent watchmaking, low or strictly limited production numbers certainly help determine if a watchmaker is independent or not. Whether or not an independent watch should be made by hand is another question entirely, but one that does not define independent watchmaking – rather, the maker is distinguished by how they choose to use the tools at their disposal.

Creativity vs. Tradition

A Laurent Ferrier Galet Classic Microrotor (left) next to an MB&F Legacy Machine 101 (right) – both independent watchmakers with distinct styles, representing tradition and innovation respectively.

According to Baumgartner, “in Switzerland and France, a watchmaker is someone who is able to assemble and give function and life to parts. [However], they are not actually the creator of the vision – just someone who follows something which already exists.”

A controversial statement in and of itself, it speaks to the fierce sense of pride that these independent watchmakers take in their craft. Many often decide to follow their own path because they are stubbornly resolute in their creative vision, unable to bend to someone else’s direction. “Creativity and innovation – the freedom to create what you like, and not just what’s driven by the market – have always been the central part of independent watchmaking,” observes Corvo.

Given that the definition of independent can also be used to reference “unconventional” creations, is independent watchmaking necessarily only defined by the watches that depart from tradition in visual or stylistic ways? Are makers who follow traditional methods and ways of creating watches still considered independent?

Team tradition – makers like Laurent Ferrier and Roger Smith may use traditional methods, but that in no way diminishes their respective inventive spirits.

“Even the most traditional watchmakers express their creativity through crafting their timepieces,” says Corvo. “From finishing their movements to creating handmade dials, ‘traditional’ does not necessarily mean a lack of brilliance or innovative spirit. I believe that everyone innovates in their own way. Take Petermann Bédat, for example – they didn’t necessarily create anything new, but upgraded a traditional movement with a new escapement. Or with Kari Voutilainen, he expresses his creativity on the dial, despite his use of traditional techniques.”

Creativity, in all its forms, continues to draw collectors to this area of watches and attracts growing interest from younger collectors and the wider public. When asked why and how he became interested in collecting independent watches, David mentions that “in a world of mass production, impersonal products, and senseless consumption, the small voice of the independent watchmaker offers an outsized, very unique, rewarding personal experience.”

Up close with the MB&F Legacy Machine 101, with its unconventional dial layout and futuristic aesthetics.

Hallock concurs with this view, and in his earliest attempts to expand the brand into the West, noted that “people were most receptive to the stories. I usually got questions about what inspired the creation itself rather than anything too technical. I would tell them about the story of how MB&F was created, why the piece itself was created, and anecdotes about the production of the piece, because people don’t really know much about the production of these watches.”

In a world where big brands continue to relive their past by renewing or transforming their older bestselling pieces, as well as respond to trends in the market, independents will continue to move the world of watchmaking forward. Whether by rediscovering older techniques or reinventing and improving complications, these creators will continue to set their course for new frontiers, bringing into existence some of the most striking and intriguing new craftsmanship.

Parting Thoughts

What is independent watchmaking? Everyone we spoke to agreed that ultimately, it is the vision and the desire to go against the grain that defines the spirit of these artists.

In recent years, we’ve seen that independent watchmaking is taking a different direction. While Covid and the rise of social media have allowed more people to interact with the watchmakers, the way these creators work is starting to shift as well. Take Kari Voutilainen opening his own case- and dial-making manufacture – he is filling a niche that will allow other independents to reduce their own reliance on external suppliers, giving greater control over an area of the art that has been a huge pain point for smaller creators over the years. In addition to that, a new wave of younger creators is also redefining how we think about independent watchmaking, from the innovations of Rexhep Rexhepi to the vivid dials of Torsti Laine.

“In a world of mass production, impersonal products, and senseless consumption, the small voice of the independent watchmaker offers an outsized, very unique, rewarding personal experience.”

To close perhaps on a slightly irreverent note, what happens when an independent watchmaker dies? Does the brand continue on without them? Would that brand still be considered independent? It’s a tricky question to which we have no answer. Take for example, Breguet, Patek Philippe, or Audemars Piguet. The watchmakers that originally founded them may have passed on their names, but their manufactures no longer represent an artist’s workshop. It’s a question for the future, to see if these independent makers are able to sustain their vision and nurture a new generation of creators even after they themselves are no longer with us.

We would like to thank Svend Andersen, Felix Baumgartner, Jacopo Corvo, David, and Steve Hallock for taking the time to share their insight and experience into the complicated but exciting world of independent watchmaking.